The shape shifting of ski categories generates noise. From powder to all-mountain to free ride (take a breath), to touring and ski mountaineering (not skimo BTW), exhale…and skimo. Are these categories generated to make us purchase more skis or a method to organize the madness of ski shape and fabrication specialization? Here’s The High Route’s attempt to keep ski selection simple.

Flipping through the scores of “best of” backcountry ski listicles, one might think we are inundated with ski choices. And discerning which skis might be “best” for you is an equally overwhelming task. With quality builds and generally accepted design features for off-piste conditions, finding a pair of skis that suits you should be relatively easy. And we’ll ask it? What is “best” anyway? Certainly, a ski with durability and a quality build rise to the top, but after that, “best” is a way to manipulate das Google algorithms. (Ok. Ok. That said, Jed Porter over at Outdoor Gear Lab has our ear. He and his testers are on those skis day in and day out.)

If you can build out a small quiver of skis, you’ll be set for any condition and terrain you envision skiing. A limited quiver of skis will cost you roughly what a carbon mountain bike costs, likely much less.

However, if you are new to the sport, knowing what type of terrain and conditions you’ll be skiing in the short and semi-long term helps narrow ski selection considerably and limits the ski quiver to a single pair of skis.

To reduce the ski selection noise, here are a few questions.

Are you seeking a powder (winter) or firm snow (spring) ski? Conversely, are you seeking skis exclusively for powder, firm and steep snow, or an all-mountain build and shape capable of slaying it all as a quiver of one? Depending on how you answer, things get more nuanced. You may seek a skinnier ski for basic touring and traversing that is a capable turn ripper. Or maybe you desire a resort uphilling setup.

Next, contemplate where you’ll be using the ski. Geography matters. The Wasatch is known for low-density light powder, whereas Oregon’s Central Cascades received powder, just of the dryish mid-density ilk. For some, a true Wasatch powder ski is wider (110mm and more) and generally has more tip and tail rocker than a powder ski that will float just fine in the Oregon Cascades.

Then there’s a personal preference for how much work you are willing or capable of when moving skis, boots, bindings, and skins uphill. A longer, wider ski requires a larger overall skin, which means a larger mass. We speak holistically, but heavier skis usually handle poor conditions better than lighter skis, and beefier boots offer more downhill control than lighter two-buckle options. Considering skis, know that backcountry skiing involves moving mass uphill with no gravity assists beyond your moxy.

Seeking Powder

Powder-specific skis, 105mm wide on up, are designed to float. At speed, the ski’s tips plane above the snow surface, providing ample control to wiggle or stamp some big and wide turns with authority. Powder-specific skis offer softer front ends (read tips) with significant rocker. Often, but not always, powder skis have a corresponding aggressive tail rocker, which promotes a looser feel with a soft release coming out of turns. These are general characteristics, and you can opt from a more conservative looking (but still possibly hard charging Pagoda Tour 112 RP), or the slightly heavier, ample rockered, and an altogether more soulful top-sheet graphics of the 4FRNT Hoji. And…there’s plenty of other great options out there if you are brand loyal.

As uphillers, keep a ski’s weight in mind. The truth is pushing a 1600g+ (the + meaning 1800g is not out of the question) uphill for powder yo-yo laps all day is doable—pace yourself. Most of us at The High Route use powder skis in…powder, but we pair them with lighter tech bindings. Seeing a powder ski with a skimo race binding (120g) also isn’t out of the question. The goal is to tailor the ski-binding pairing to reduce overall weight. And in powder snow, true powder snow, driving a big and wide ski is fun in a 1kg class touring boot.

Can you have fun in a skinnier ski with less tip rocker in powder? Yes. Will you have more fun in powder with a powder specific (read floatier) ski? Smiles can be hard to come by. We’ll side with yes.

Who benefits more? The intermediate, and certainly a beginning backcountry skier, benefit more from a surfy powder ski. These skis often are easier to handle. In lower angle powder shots where it’s more difficult to harness speed and get the ski planing, everybody benefits. If breakable crust, zipper crust, and heavy snow (not ideal conditions) are on the menu, powder skis can help too.

Seeking…All Mountain

All is a pretty damn wide-open classification. It’s sort of like “best of.” Anyhow, this category of touring ski has origins in the on-piste marketing world. Let’s take a single day at the local ski area. It’s a bluebird day right after a storm. There are powder shots to be had. Those get skied out after a few cycles of the high-speed quad. Then there’s tracked powder. And too, you might carve some turns on trails corduroyed by the early AM snow cats. As the sun continues its arc, you might also find heavier mashed potato snow (powder happens in spring too).

One ski to rule them all, or at least all conditions: This is the aspirational all-mountain ski. As we noted, finding anything high performing in all conditions is aspirational. But finding a ski that is fun in most conditions is plausible. All mountain in the backcountry is a lot of mountain. Take note. A wide ski with lots of tip and tail rocker will perform less nobly in firm and icy conditions. Conversely, a skinner ski with less rocker and a stiffer overall flex shines in firm snow and less so in deep powder.

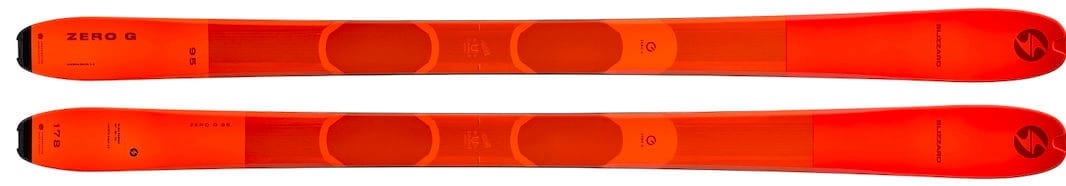

Skis with less tail rocker (straighter/stiffer tail), a 95mm-107mm waist, and some modest tip rocker are our all-mountain ski attributes. These skis can handle with aplomb, much of what is thrown at it. Here’s an example:

For someone seeking an all-around ski that thrives in powder and more variable conditions and is passable on hardpack, a ski like the Atomic Backland 107 will keep you smiling. Again, many brands make a ski similar to the Backland 107. Many of us at The High Route would argue, though, that a ski this wide, and likely in the lengths you want for powder snow flotation, is too much ski in the spring when chasing corn cycles. So if your all-mountain includes corn cycle missions, in the end, you will likely pair this type of ski with a skinnier and shorter, and perhaps less tip-rockered plank.

Who benefits from the all-mountain ski? It becomes a hair-splitting dilemma, do you shift skinnier or wider in the ski selection spectrum? If you store skis when the local mountain biking trails open (or skip town and head to the desert for mud season), trend towards 105mm. If ski touring consumes you and the season extends into April, May, and beyond, the 95mm end of the spectrum calls your name.

Ski Mountaineering

The ski mountaineering class gets some out there all hot-headed. If that’s you, maybe you have a precise definition of that term. Maybe ski mountaineering means sharps like axes and crampons and things to get tangled like ropes. It may mean traveling through the mountains on skis. We’ll use ski mountaineering more universally; you seek adventure in the mountains. However, it doesn’t categorically mean lines 45 degrees and steeper; it could mean flats to mountain passes to gradual descents.

This category of ski stems from 80mm to 95mm underfoot. And they shine in firm and steeper terrain. The tails can be near straight with little rocker, while mid-sections are traditionally cambered and stiff, and the front end is stiff, too, with a bit of rocker. Better edge hold in firm conditions is the upside of this rigidity and modest rocker (the effective edge is longer than an equal-length powder or all-mountain ski).

Ski mountaineering skis are usually lighter, too—anywhere from 1000g to 1300g, which also helps with big ascents and swing weight when jump-turning.

Who benefits? We are using the term ski mountaineering broadly. You can use this class of ski to good effect without ski mountaineering. For example, those seeking a light, nimble, and sassy-carving resort uphill ski benefit. Those carrying 40-pound packs and eyeing a multi-day traverse benefit. If you are on a one-day push, these skis work. And if remote-line steep skiing gets you all bunched up in a good way, even if you aren’t rappelling into the couloir of the day, you’ll want a ski mountaineering ski (but you already know that).

Because these are lighter and stiffer skis with longer effective edges, they usually incorporate carbon into the construction. In chundery conditions, these skis can get pushed around.

Lastly, the sizing— often, people downsize when choosing this type of ski. One reason is a smaller ski is a lighter ski. This ski category is easier to carry on the pack and ascend technical ground. In tighter chutes, a shorter length is also handy; they are more nimble in chokes and easier to jump turn.

Our writers, who trend into the low to mid-180s for powder ski length, size down to ~170cm for mission-specific ski mountaineering.

SkiMo

We know of a Prius floating around Bend with a bumper sticker (placed on the car by Barry and made by his friend Matt) that reads, “SkiMo is Niether”. No matter where you stand on that issue, whether skimo is or isn’t one of those or a blend, we can say that the typographical error “niether” is neither correctly spelled nor used in any English-speaking countries. It thus renders the sticker’s point moot and unsubstantiated.

What is skimo, then, and where does it leave us? As it primarily exists, we’ll call it an organized Lycra-sport at ski areas that can involve timing devices and HRMs. And in some iterations, it can involve legit (meaning attempt at your risk) mountain travel. But the gear of those hustle and bustle cats has its place in backcountry skiing.

The skis are rigid, ~65mm underfoot, and available in sizes like 160cm. The weight is speed-inducing, landing between 620g-720g/ski depending on the size and model. With skimo skis, durability can be an issue. Space-age materials are stiff and light, but those qualities don’t necessarily translate into long-lasting. Skimo skis can be considered specific tools for a particular job—not a daily driver unless you aim to replace the skis every few years.

Who benefits? For those resort uphillers looking for the lightest setup, skimo skis paired with a race binding and skimo boot are ideal. You’ll float uphill like a butterfly, and if the trails are groomed, carving on these skinny-short boards is fun. If and when the terrain gets rowdy, get ready to buckle up.

Outside of resort uphilling, we do find some excellent uses. If you live in a region where local snowmobile clubs groom trails and allow non-motorized users, then skate skiing on a race-ready skimo setup is blissful, and since it’s not the local cross-country area, you won’t be yelling track at any skiers. It is also not uncommon to see highly trained athletes attempt speed ascents/descents and traverses on skimo gear. If you can time the cycle right, a speed ascent/descent while nailing corn on the descent on a super light ski is king.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.