I’ve had an opportunity to use onX Backcountry for the past few months. My primary reason for learning more about the platform is that onX has released a few new layers on their backcountry platform. According to onX, the layers can help winter backcountry users plan and execute safer trips.

onX has added three new layers of interest: ATES, Avalanche Runout, and Avalanche Potential Release. According to onX, they use many different inputs to derive the ATES layer, which includes the runout and potential release layers.

The onX site states, “This initiative involves compiling existing information and firsthand observations used by an avalanche and snow safety experts to assess local terrain avalanche risks, constructing geospatial models that predict avalanche release areas and potential zones based on factors like slope angles, wind patterns, and forest density. This resulting ATES terrain classification offers crucial insights for backcountry users.”

Full disclosure: onX provided a two-month subscription with the new layers activated.

Avalanche Terrain Exposure Scale Layer (ATES)

I’ll quote myself from a previous article on The High Route. “The tried and true public ATES paradigm uses three classifications: simple, challenging, and complex. Depending on your objective, skills, and experience, an ATES rating provides some historical context to one’s relative exposure to avalanches. An ATES classification is static: it does not change due to a day’s or week’s forecast or known instabilities—in other words, the likelihood of an avalanche occurring during your tour on any given day. The ATES becomes a reliable and fixed system we can rely on. The goal is to give the public user a tool to help them differentiate between different trips and, combined with a current forecast, choose a trip that fits the conditions.” Again, the ATES scale and any ATES color coding you may see on a digital map or a ski tour atlas are independent of the day’s forecast.

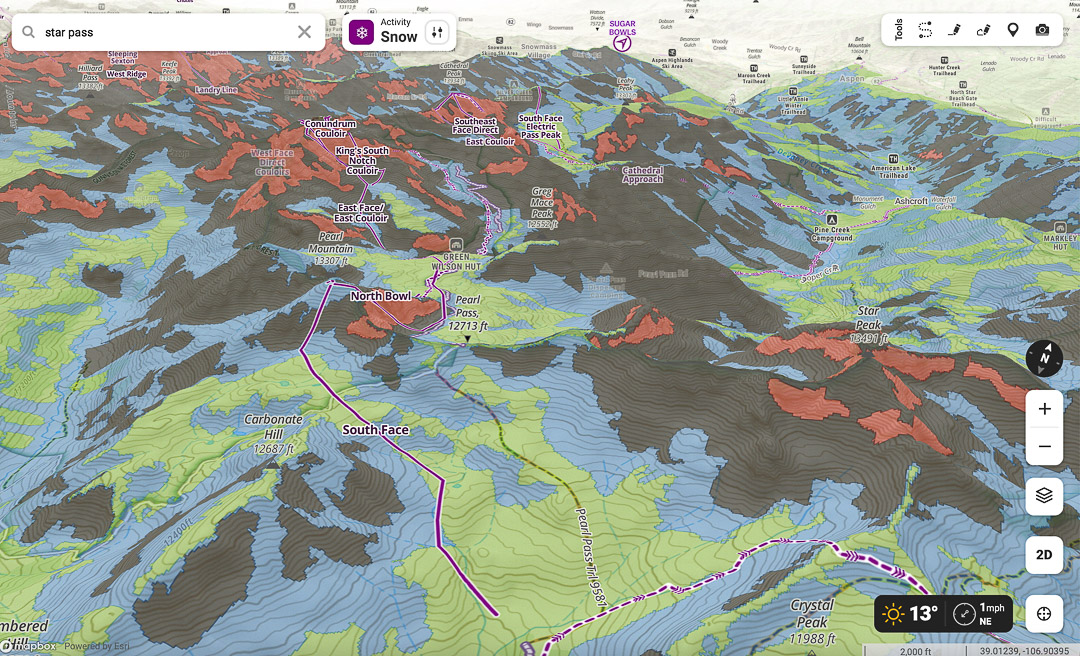

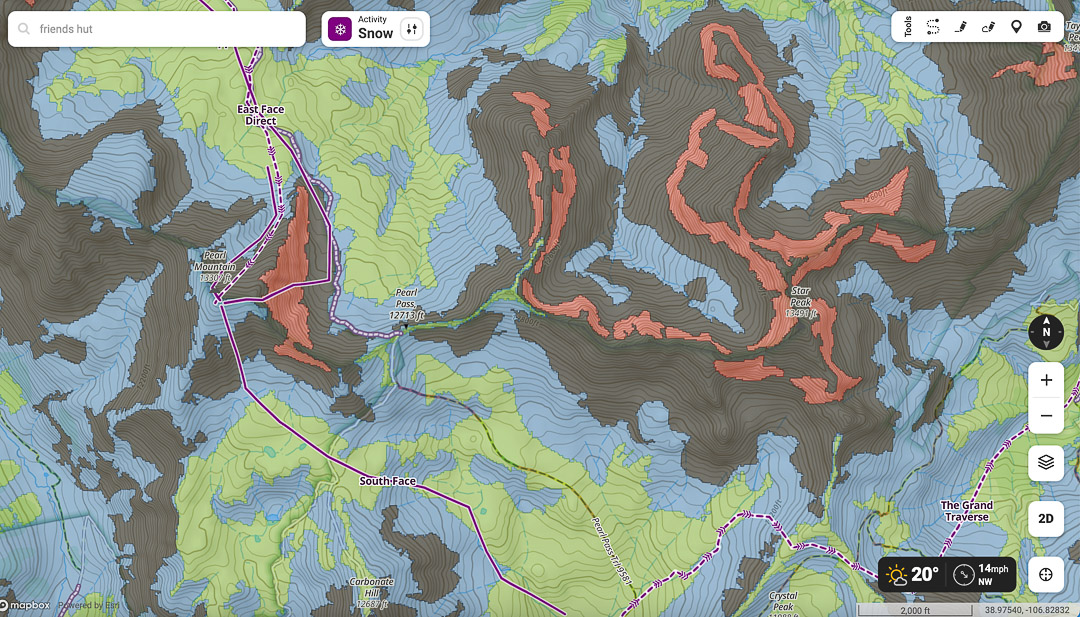

The onX ATES layer has been introduced in specific Colorado, Montana, and Utah zones—plans are to expand coverage in those states and broaden it to Washington, Wyoming, and Alaska. The map below shows onX using the new ATES rating scale: Colors code for the terrain’s avalanche exposure: Simple (Green), Challenging (blue), Complex (black), and Extreme (red).

Avalanche Runout Layer

onX states, “The Avalanche Runout layer visualizes the potential runout zones of an avalanche. onX Backcountry worked with local avalanche professionals to understand typical and historic avalanche alpha angles for each unique region. These inputs from local professionals are directly reflected in the model and runout visualization for each individual region.”