As winter approaches in the Northern Hemisphere, we offer up a think piece to get us all considering the decisions we make in the hills.

We are a data-driven society, and we are a society in the grips of technological determinism where everything should be quantified and optimized. The language of work and leisure is suffused with the language of technology, and yet, when we move through the mountains, we are operating in the domain of uncertainty with limited physical and cognitive resources. The confidence that weather and avalanche forecasting give us, the comforting glow of smartphone technology, the satisfying vocabulary of scientific and statistical terms—all of these combine to obscure the reality that the natural world, while completely indifferent to us, is also wildly unpredictable. However, many are determined to push the square peg of scientism into the round hole of reality.

This was evident in a viral social media post castigating the climbing community for its apparent poor communication and a general lack of honest appraisal and language around hazards. The post began with an equation which many people would assume has some basis in statistics, and then continued with a statistical comparison between driving, which you would also expect has some empirical basis. While I think the spirit behind the post—that we shouldn’t minimize the danger of mountain pursuits—is a valid one, the appeal to the authority of data is alluring and misleading. Although this might play nicely in a keynote address or Instagram, it has limited utility. It might sound like the right kind of claim, and scientism often has the character and form of an empirical idea, but not all bird shaped things are birds.

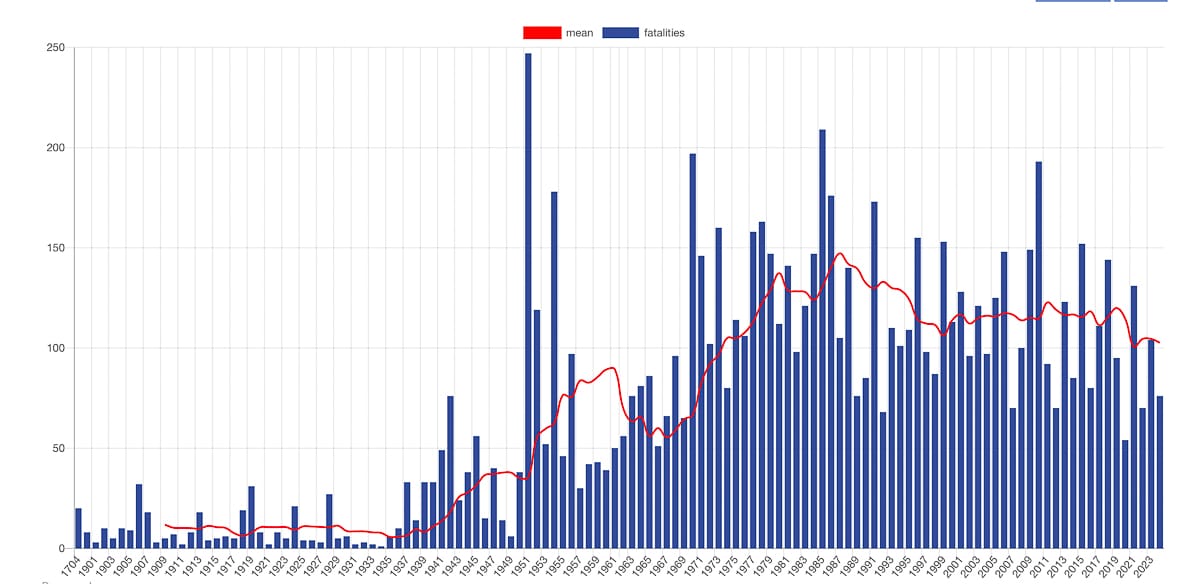

Most skiers and climbers would correctly assume avalanches pose the greatest danger to backcountry travel. If you had to ask at what rate avalanches kill people, I am sure that many would overstate the number. According to European Avalanche Warning Services (EAWS) data, deaths by avalanches are trending down despite an increase in backcountry travelers. U.S. data shows a similar trend but includes mechanized backcountry travel, which makes comparing with EAWS more difficult. There are various estimates of backcountry participants, some placing the numbers in the millions. Whatever number you choose to believe, this reduction in mortality has also coincided with an enormous increase in riders. It’s hard to draw any other conclusion besides this: education and forecasting are behind the reduction in avalanche mortality. Advances in our understanding of snowpacks and the mechanisms of avalanches have made the public communication of avalanche danger more salient and accurate. What we have, then, is a paradox for the marginal participant. Skiers and climbers overstate avalanche danger but, at the same time, are lulled into a false sense of security by avalanche forecasting

As beginners we are often told by friends, mentors and Reddit strangers that doing an introductory course in avalanche safety is de rigueur before we set out on our human-powered turn career. We aren’t told why, however. Why should we prioritize analytical knowledge? Why should we prioritize practical skills around safety like snowpack sampling and crevasse rescue? And even if we have ticked all the pre-skinning safety boxes, we often aren’t told that this knowledge, and the skills associated with it, degrade almost immediately after we have assimilated it. Perhaps there is an assumption that the avalanche forecasters have our backs. But our safety in avalanche terrain is contingent on forecasters and our own analytical work and experience. Successful crevasse rescue is contingent on the abilities of the people at both ends of the rope. Analytics and forecasting are contingent on each other because the mountains are not orderly and predictable places.