A bit of hand-holding would be in order this week. About a ½ mile downriver from the house is the 2023 International Snow Science Conference (ISSW). The ISSW is, for all practical purposes, an academic conference with a strong tilt toward a topic we are all likely interested in—avalanches and how to predict and avoid them. There are some heady presentations. As an enthusiast, there are also excellent takeaways and new material to absorb. We’ll be highlighting some of those in the coming weeks.

Hats off to the ISSW organizers—they should be proud. And thanks to Aaron Diamond for editing assistance.

First up is a paper by Grant Statham and Cam Campbell titled “The Avalanche Terrain Exposure Scale V.2.” We spoke to Statham, a mountain rescue specialist and avalanche forecaster for Parks Canada and an IFMGA guide, to learn more about this new work..

ATES Background

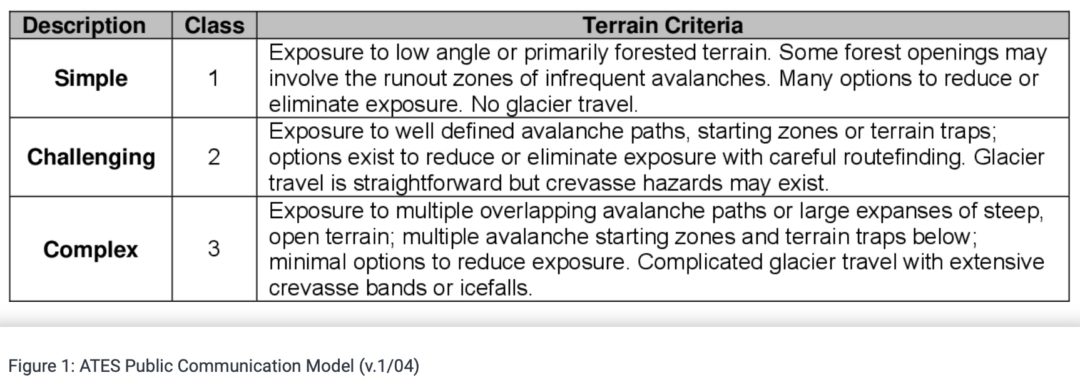

The tried and true public ATES paradigm uses three classifications: simple, challenging, and complex. (See chart below.) As noted, depending on your objective, skills, and experience, an ATES rating provides some historical context to one’s relative exposure to avalanches. An ATES classification is static: it does not change due to a day’s or week’s forecast or known instabilities— in other words, the likelihood of an avalanche occurring during your tour on any given day. The ATES becomes a reliable and fixed system we can rely on. The goal is to give the public user a tool to help them differentiate between different trips and combined with a current forecast choose a trip that fits the conditions.

The authors write about the original ATES, “ratings are determined using both qualitative and quantitative analyses and result in a subjective measure of the degree of avalanche terrain exposure on a discrete five-level scale. Unlike the transient nature of avalanche hazard assessment, which rises and falls with the changing weather and snowpack conditions, ATES ratings are based upon constant parameters that do not change (e.g., slope angle, exposure) or change slowly (e.g., avalanche frequency, forest density), resulting in a static, unchanging terrain rating.”

Although the ATES has been widely adopted in Canada, it has yet to gain a critical foothold in the U.S. Some of you might be familiar with Beacon Guidebooks, a Colorado-based ski atlas and map company, which applies the ATES effectively in its products. Some regions in the U.S. use the system as well. (According to Statham, the implementation of Auto-ATES might change this dynamic. “We have an algorithm now that does the terrain grading automatically. So that changes everything because now it can be done easily,” said Statham.)

Two devastating avalanches in 2003, one of which killed 17 young students on Rodgers Pass, prompted the development of the ATES.

“It was after that, and, upon review of that avalanche, it became clear that we didn’t have very good tools to tell the public, believe it or not, that this particular trip is more risky than that particular trip,” said Statham. “We had no way to differentiate between the magnitude of the trip [from an avalanche perspective] for the public, which seems like a very basic thing you want to be able to say. This system was designed to meet that need.”