The Thought Experiment

Try this for a backcountry skiing thought experiment: a “famous” local has been in town for eight or nine years. You couldn’t pick them out of a lineup, and most certainly not costumed in the season’s latest bro-wear on a cold day: big goggles, go-proed helmet, just the right amount of baggy in the baggy jacket and bibs.

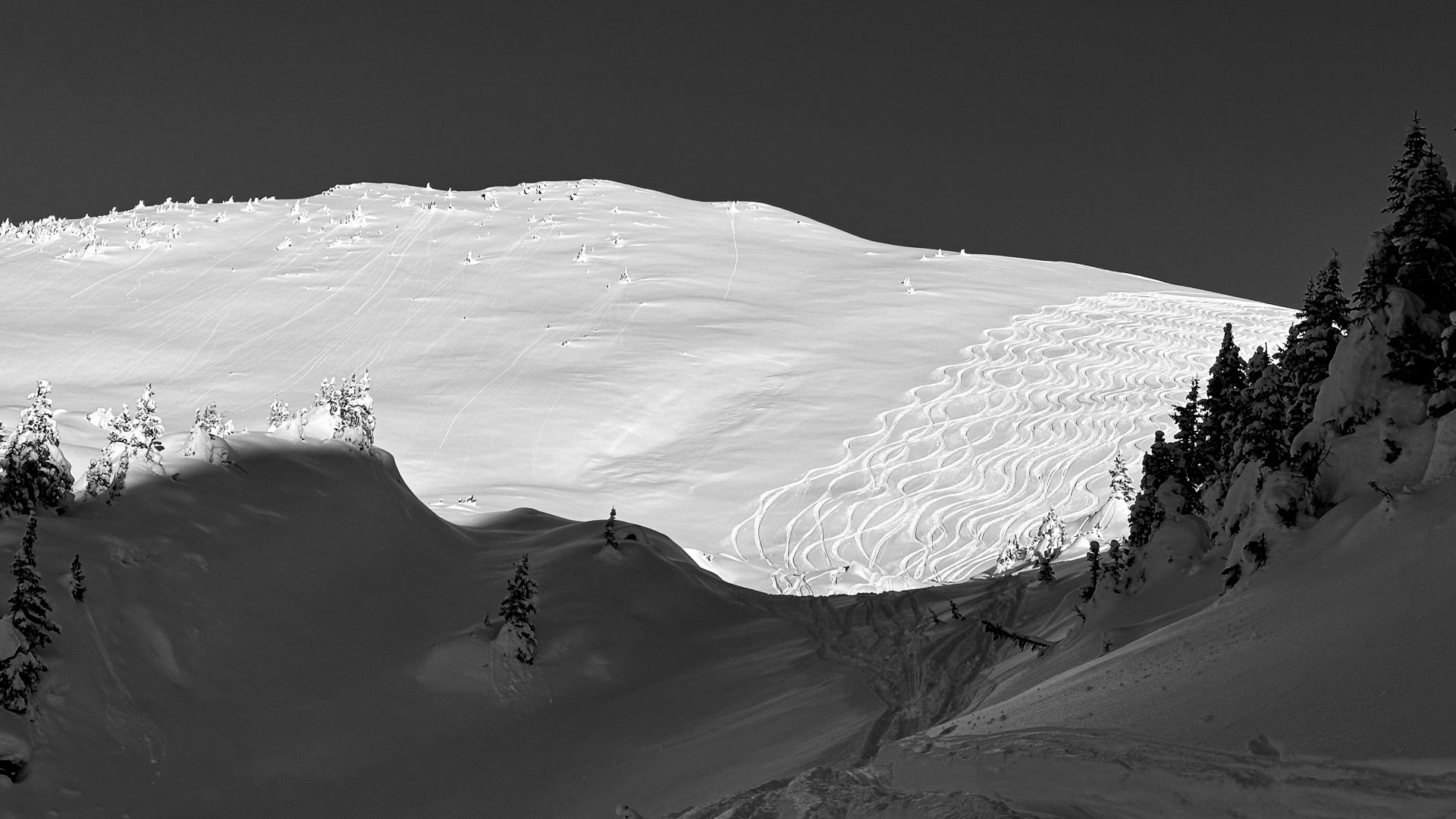

After a cold dump and shred, late one evening, or sometimes two weeks later (it’s apropos in some circles to delay social posting about a pow day until everyone is getting skunked), the skier posts an IG self-salute of the day’s gnar. You’ve seen this self-salute before. There’s the speed check turn, the cursory pause for the running sluff—then a point-em-and-straight-line canvas painting. Sometimes, an air interrupts the artistry or adds to the mark-making. You decide.

On its face, there’s not much going on here. It could be a sponsorship obligation and a paycheck.

Imagine the skier and his videographer routinely post stills and reels from this “locals” spot with some calculated edits. There’s just enough footage of the slope and surrounding area to get a tease of the locale; they crop out obvious landmarks. With that landmark editing, are we clueless about the pow stash’s whereabouts? Not really. You live here too and know that with open eyes and personal tours just slightly off the beaten skintrack, the precise location is clear. Your region has a limited supply of mid-winter steepish skiing and rock drops.

This same local sours when others post about these ski zones, even when editing out location-specific features and no geotagging. Like the rest of us, they can decipher where these shots originate. Lastly, to make matters worse, they stink eye, or verbally confront, those outside his crew when they see you have a tasty day, just like him, at their preferred ski zone.

Who, if anyone, gets to police local spots? Who gets to “protect” our scarce resource, powder, for select locals? Is it the best local free skier who has lived here for less than a decade? Is it the sponsored athletes with a following? Is the true local who has been yo-yo-ing for 20 years and feels entitled to park their sled just beyond the wilderness boundary the enforcer? Should localism even be a concern?

I don’t have those answers. I also don’t have the answer (only opinions) regarding social media posts featuring the hyper-local powder stash and trying to disguise the hyper-local spot to make it appear as any old spot. There’s a lot of effort and performance going into that geographic masquerading. If you don’t want people to know, don’t post.