The this part in our series on the PdG is an opportunity to see how one team of motivated individuals finished the race in good form and remained friends. If you seek an end-of-season goal, or even a year-or-two-out goal, consider the PdG a must do event.

If you’ve made it this far (see Part 1 and Part 2 and still need to figure out whether the PdG is for you, I’ll again say that you should do it. Yes, it’s a bit of a commitment but it’s worth it. If you’ve done any of the bigger North American races (e.g., Powder Keg, Power of Four, Grand Traverse), then the PdG is your logical next step. If you’ve skimo raced at all, it’s still doable with some effort. And even if you’ve never raced but are an avid and fairly fit backcountry skier with decent ski mountaineering experience, the PdG is definitely within your capabilities.

Simply put, the PdG is accessible to a much broader range of participants than die-hard skimo racers who practice double skin rip transitions. Yes, less experience will mean a more concerted and consistent effort is needed to prepare. But as usual, the right attitude can make up for a lot. The following recap of Team Tahoe Skimo’s experience in the 2022 PdG is that of a team that, in hindsight, seems pretty representative of the average.

How it went

Ready, set, …. Team Tahoe Skimo has weathered the travel, logistics, and the training. Moments from race start.

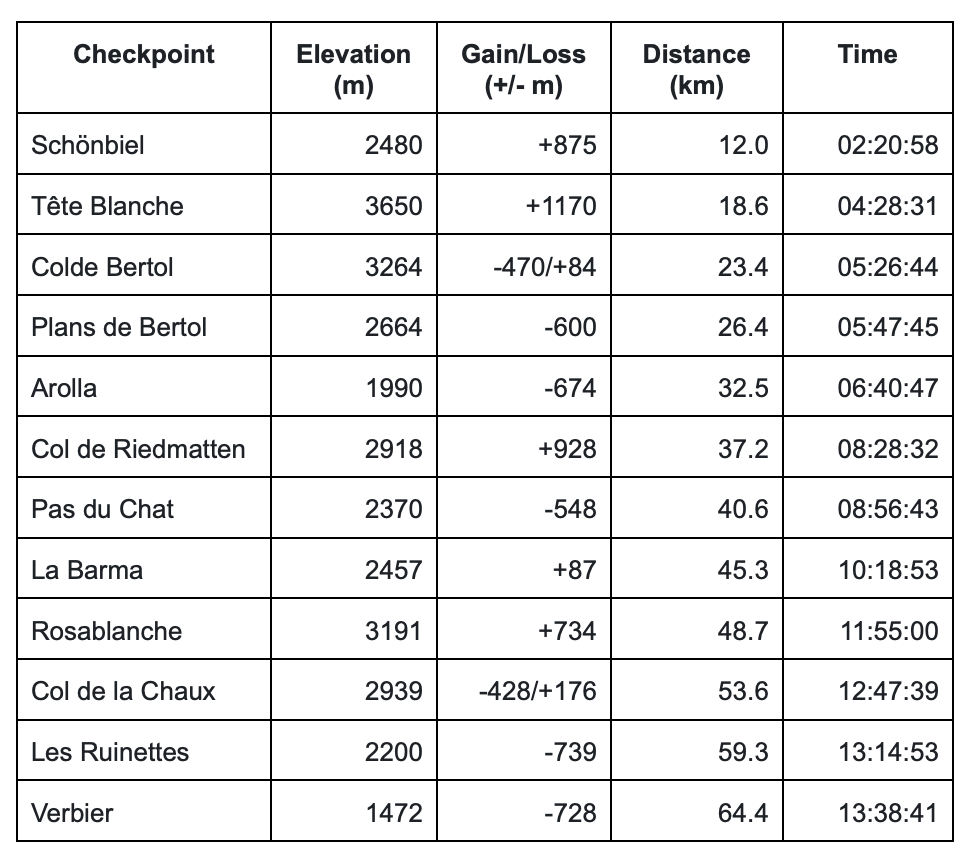

We started at 11 PM, running up Zermatt’s Bahnhofstrasse with bar patrons and other late-night spectators cheering us on. With the start of the Z1 race bumped back a day due to weather, the organizers also moved everyone’s start times up by 30 minutes and relaxed some of the time cuts. With the lack of snow, the organizers had to alter the route slightly, and it ended up being just under 65 km instead of 57.5. While the race always starts on foot, and some dirt hiking is normal, we did the first 6.5 km in running shoes (which the Swiss Army kindly collected and donated to charity). Andy was psyched about running, but Matt and I were less so.

We then settled into a nice skinning rhythm to the rope up at the Schönbiel checkpoint. A word on the checkpoints (Control Posts in PdG parlance): These are elaborate mountain camps installed for the race by the military—roped off areas with shelters, generators, high-powered lighting, and lots of staff to direct you. The PdG is said to be the Swiss military’s largest operation of the year, and it shows. All patrol members (teammates) must pass through a chip scanning together at each checkpoint.

We planned to keep the pace workmanlike and reserved to Arolla and then see if we could push more during the second half. We climbed the course’s first booter up the Stöckji Wall onto the Stockji Glacier, and I flashed back 20 years to that whiteout descent when the course marking saved us. Those markings were again helpful in avoiding the numerous crevasses on the never-ending and ever-steepening skin to the Tête Blanche. For perspective, the elevation gain from the start in Zermatt to the Tête Blanche is nearly half the vert of the entire course. So, you start the PdG by almost climbing the Grand Teton or Mt. Shasta.

I suffered during the last 90 or so minutes of the climb as Andy pushed the pace to the course high point just shy of 12,000ft. I should have spoken up for a slower pace and paused to put on my puffy sooner. It was cold, maybe around -15C. It turned out that we were all silently suffering in the same way. But we were passing lots of teams, and each of us independently got sucked into thinking the higher pace would warm us. We put on nearly all our clothes when we ripped skins for the descent of the Tête Blanche. And then, two turns in, Andy’s headlamp failed. So even with some shallow cut-up powder to start the descent (it didn’t last long), the roped-down skiing was, shall we say, challenging and slow. I’ll say again how impressed (and a little depressed) I was by some teams flying by us with well-oiled communication, coordinated skiing, and artful rope management.

We started to adapt to Andy’s braille skiing when we hit the short climb to the Col de Bertol and another checkpoint, where the rope comes off. The long descent to Arolla started as breakable crust and turned to a well-peppered hardpack. And the course revealed its serious side fairly early in this descent, with a Swiss soldier appearing seemingly out of nowhere and waving a flashlight for an abrupt hard left turn onto a single file traverse track above a drop off. It was too dark to see the full exposure, but the netting suggested it was substantial.

Another team later reported seeing a racer in front of them eat it hard to make it onto the traverse. The rock slalom continued as the horizon started to glow with the coming dawn. We eventually ran out of snow and had to walk to the Arolla ski station.

Halfway. 6:40 of elapsed time, slower than we’d hoped, but we felt we still had a chance at a 12-hour finish. Based on what, I’m unsure.

The starting gun for the A1 race went off as we refilled hydration bladders and otherwise took advantage of the first of the only two official aid stations on the course. I was concerned that I’d gone too deep on the final part of the climb to the Tête Blanche, but some tea and biscuits sure helped. It’s worth noting that the aid stations are not like those at many North American ultra events. You can get tea, broth, Cokes, Swiss chocolate bars, maybe some pasta. And there are only two stations in 57+ km. It’s best to bring your own race rations.

The start of the climb to the Col de Riedmatten goes straight up the piste next to a chairlift. We were now mixing in with the A1 course racers and passing quite a few who were sounding and looking annoyingly fresh. That was until the piste steepened, and the skinning became super slick.

Our initial “digestion pace” allowed us to avoid deploying the harscheisen (ski crampons). We tacked off the piste briefly at the steepest part to reduce the track angle and increase the traction. The piste ended, and we were back into the high and wild alpine in what seemed like the blink of an eye. Fortunately, I felt some recovery kicking in, but we wouldn’t be increasing our pace like we thought we might. The booter that finishes the climb to the col had stretches of bare ground with grassy hummocks, which felt strange in a ski race.

The initial descent of the Col de Riedmatten was also bare and sketchy. The terrain was rocky and loose. Some of it was pushing Class 3. There were handlines, but it felt crazy to be trying to blitz down this in a line of others above and below intent on doing the same. You could pass, but not without elevating the pucker factor. A Col de Riedmattene type of descent simply would not be in an American race.

Once the skis were back on, the technicality of the terrain continued. More rocky, refrozen surfaces and tight turns. Another safety-netted traverse. Eventually, this funneled into the Pas du Chat at the south end of the Lac des Dix. There were a bunch of Swiss military and at least one Swiss mountain guide metering traffic to one skier at a time. We employed some cat-like agility to traverse and descend the steep, exposed gully features that crossed the lake outlet.

Once across, we faced a key decision: skin or skate the traverse above the lakeshore—it’s a deceptive false flat. While skating is generally faster, you’ve got to be able to sustain it. If you blow up and have to transition to skins, you’ll easily lose whatever you gained. The conditions matter, too. A fair amount of the traverse is sidehill, and it’s nothing like the skating lane at your local Nordic center. You’ll need a strong right leg and do some double poling and marathon skating. So consider your skate skiing ability. We started conservatively by skinning but quickly ripped skins and skated about the last two-thirds of the traverse.

For Tahoe Skimo, the Rosablanche booter was situated roughly 10 hours into the race. Photo: Berthoud Photo

The course then swings west away from the lake and up a bit to the La Barma aid station. The sun was beating down, and cold drinks (water or coke) and fruit pieces were available. Now, 10 hours in and unable to push hard, we didn’t rush this aid stop since the climb of the Rosablanche, including the reputed 1000-step booter, awaited us. We made sure we were topped up and ready.

It seemed evident by then that 12 hours wasn’t happening. But it was like, “Whatever. Let’s just keep grinding and finish strong without blowing up.”

With undeniably heavy legs, we stayed steady, if not fast, with our skinning pace. It became clear that my younger teammates were now humoring me. I tried to soak it all in—a stream of like-minded skiers as far as you could see ahead and behind, flowing through quintessential Swiss alpine terrain and celebrating the suffering. Acknowledgments of comradery were shared in words or smiles or grimaces as we passed and got passed.

The Rosablanche booter perfectly culminated my Euro skimo romanticism and sentimentality. At the base, you could hear an oompah band playing and a mass of spectators ringing cowbells and cheering. Above, you saw a Swiss-engineered stairway to heaven, with hand lines, parallel slow and fast lanes, and a backed-up queue of racers in each. We got in the fast lane, but the pace and the inability to pass allowed some recovery.

The top of the Rosablanche is close enough to Verbier that a huge crowd gathers and lines the course. Some tour up there, and others get a helicopter ride. The course is narrow atop the mountain ridge, and the tunnel of spectators feels like the Tour de France. It’s loud as they congratulate you – “Bravo! Bravo!” and hand up drinks and snacks. And to the random dude who gave Andy and me a Coke and cookies, merci beaucoup. Many teams stopped for photos with family and friends there to greet and cheer them on. It was so crowded and chaotic that even with barriers separating the course from the spectators, finding a place to transition took some effort.

The descent of the Rosablanche and final short climb to the Col de la Chaux are vague and unremarkable in my memory. We got our first legitimately good, soft snow turns off the col before we hit the pistes above Verbier. On the groomers, Matt was ripping smooth GS turns on increasingly sloppy snow, and Andy and I hung on as best we could. The piste went underneath the Bec des Rosses, the Xtreme Verbier Freeride World Tour stop venue, and then past the Cabane du Mont Fort hut, where a sign for food and beer triggered thoughts of post-race refueling. But then skiing was interruptus, as dirt patches forced jogging and remounting.

The course enters Verbier and leaves the snow at the telecabine station on the uphill side of town. It’s about another kilometer of cobblestone streets downhill in ski boots to the finish. Spectators lined the streets, most enjoying lunch, a beer, or a coffee on a warm sunny day. It felt stupid to be walking when they stood up and congratulated us. So that, combined with a not so subtle request from Andy, and we were jogging the rest of the way. Arrivee! 13:38.

While way over our estimated time, I was satisfied with 13:38:41 in the conditions we had. The winning time for the civilian without guide category (P4) of the Z1 race we were in was 9:30. The last finishing team in our race came in with a time of 18:25. The overall winning time was 6:35 for the pros who raced in Z2 on Friday. The course record is a mindblowing 5:35 set in 2018 by an Italian team of the top ISMF World Cup racers. The difficult conditions meant times for our race were 20 to 30 percent slower than the fastest times. In more normal conditions, 12 hours or faster seems doable for us.

After a finish line photo, a congratulatory handshake from the PdG Commandant, and a heartfelt thank you to him and his troops, we entered a mass of stinky lycra and tired bodies with big smiles. We turned in our timing chips and PdG-issued items and found a place to sit down (ok, collapse). The finish area compound had beer and food tents where teams celebrated with welcoming families and friends. We sat and drank water and tried to avoid the onset of inertia, knowing we still had to pick up our luggage from Zermatt. We managed that and changed into street clothes. Showers are available since some racers clean up, drink and eat the complimentary beer and meal for finishers, and hop on the train home. We enjoyed the beer and meal but faced the hardest part of the day. We had to trudge the reverse of the last kilometer of the course, dragging our luggage back uphill to our Air BnB next to the gondola where we stepped off the snow earlier. Ouch.

How we did

We ended up 38th of 180 teams that started in the civilian without guide category of Z1. We were 67th of 288 teams of all categories that started Z1. 111 of those 288 teams didn’t finish (either dropped out or missed a time cut) or had a teammate drop (finished with only two members), in which case the team doesn’t count in the finish rankings. We were 26th of the 132 teams in the Senior II division (combined age of 103-150), which was better than I expected. If you’re curious, a Swiss team won the Senior III division with a combined age of 159 (56, 53, and 50) in an astounding time of 10:31:17. Chapeau! A reminder that you’re in fast company racing the PdG.

Final Thoughts

There were many moments where I found myself in awe of the course and the mountains it traverses, of my fellow racers and the huge number of them, of the Swiss military and their effort to pull this off, and… And I’d smile at the vibe coming back to me that says “Hey, this is just how we do it here.” So I’d take another step or make another turn and keep going.

To the PdG Command of the Swiss Armed Forces: Merci, danke for organizing and presenting this amazing race. Thank you skimo.co for the race suits and support. And most importantly, thank you Matt and Andy for patrolling with the Chef and agreeably racing at a pace I could handle.

If you’re thinking about it and want to chat, I’m happy to. Just know that I’ll try to talk you into it! More PdG info, and other perspectives can be found here:

- A primer and prep article and a race report from another American team in the 2022 PdG. Allen Taylor, Ben Peters, and Sam Lien passed us at some point, but neither Allen nor I recall where. Articles linked here and here.

- Ben Tibbett’s 2014 race report with an abundance of his great photos.