Moving across a mountain range on skis is a blessing. A ski traverse, for many, is the penultimate. Seek adventure, light out on a traverse. Here’s the first part in our series Planning a Traverse.

The Planning a Traverse series is a resource to help you…plan a traverse. We don’t take traverses lightly. The title here, including the term “first steps,” has some intent; it’s a multi-part process. Part planning. Many parts planning. And part doing. And part learning for the next traverse. We hope, through careful planning, you can successfully execute a traverse. Yet, we’re saying it (or at least writing it); we are not responsible for you while you plan a traverse or for the eventual traverse outcome.

Godspeed.

Just like a little human, learning to walk is critical. There are stumbles and bumbles along the way. We expect those. Before you know it, the bipedal thing takes over. It’s like that on skis too, and so too, by extension, is pulling off a traverse. What we are saying is to start small. Be success-oriented with your first traverse goal—choose a point-to-point or a circuit you can pull off in a day (24 hours). By starting small, you set yourself up for success when you inevitably reach out of your comfort zone.

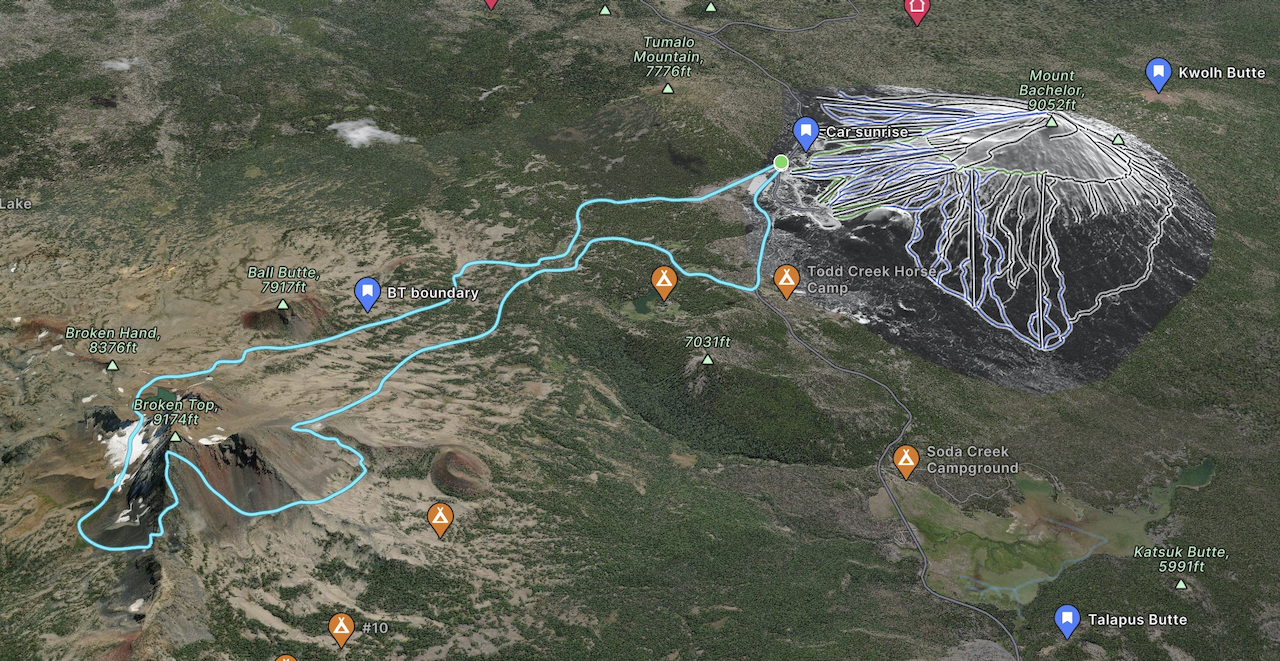

In backcountry skiing, we mostly think of traverses as epic point-to-points. There’s the Chamonix to Zermatt Haute Route. Bugs to Rogers. Sierra and Wind River traverses and pushes across the Presidentials. If you live in a mountain town, even one with conical shield volcanoes, you, too, have a traverse or three on offer. Although, the point-to-point missions are what we think of as the classics, they often require some snafu-type logistics for first-timers. As we’re taking first steps—we’ll stick to first steps—there’s plenty of time to be young and brash on the second or third traverse objective.

Consider a Circuit

Consider a circuit to keep it simple. Start and finish in the same spot. A trip like this requires less planning and coordination. Circuits are also key in the event you must turn around. Someone could take an accidental dunk in a creek and that partner needs to pivot. Or a storm rolls in, or visibility is bunk. Pivoting, especially if you are less than halfway, is an easy decision to make. We’re taking a bias stance and claiming a circuit is more interesting than an out and back. An out and back has a sense of a preordained outcome — you’ve already been through the terrain once and know what to expect. In challenging ourselves, we want some calculated risk involved, which means to some degree, an unknown outcome. What better way to embrace this than covering new ground but ending up right where you started? There’s some Zen in there when you consider the power of a rambling ski circuit. And really, we want a positive outcome so you can start planning the next traverse.