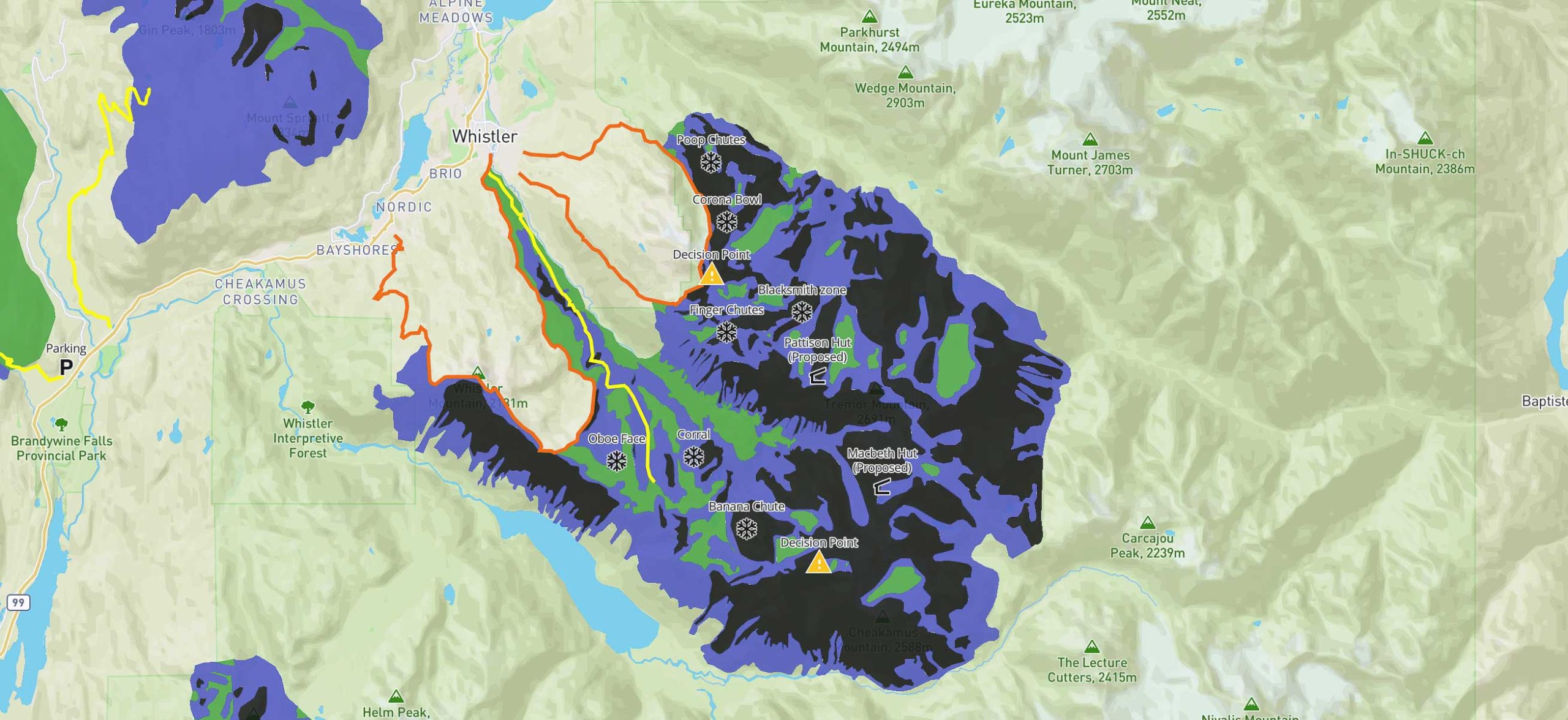

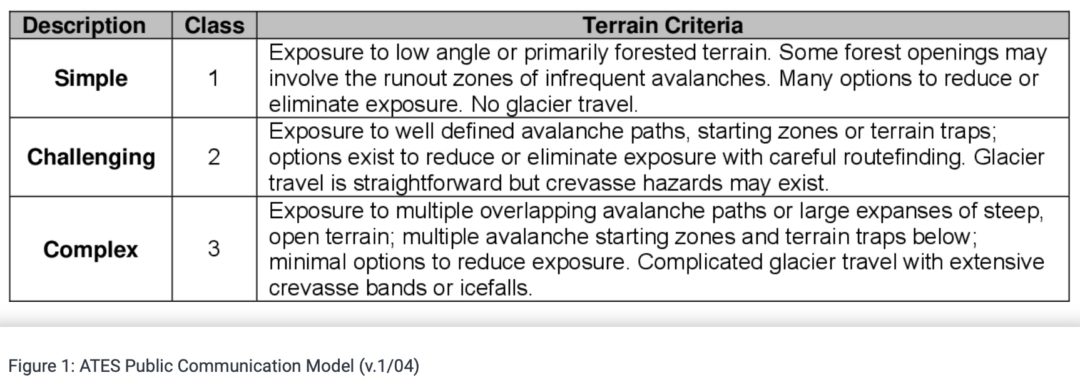

Last Friday concluded the ISSW2023, or the International Snow Science Workshop. We published a piece on ATES v.2, which was presented at ISSW as a new template for the well-established ATES, also known as the Avalanche Terrain Exposure Scale. In short, the ATES scale describes one’s exposure to a potential avalanche. The initial version of ATES uses a three-tiered scale communication model: simple, challenging, and complex. Each description is aligned with a color for easier ATES applications on maps where green is simple, blue is challenging, and black is complex. As explained in the ATES v.2 article, an ATES description is static; it does not change with a daily or weekly avalanche forecast.

When ascertaining information about the terrain and designating an ATES description, avalanche professionals use a technical ATES model. In the original ATES technical model published in 2004, we see below that data on slope angle, interaction with avalanche paths, and exposure time, among other parameters, are considered.