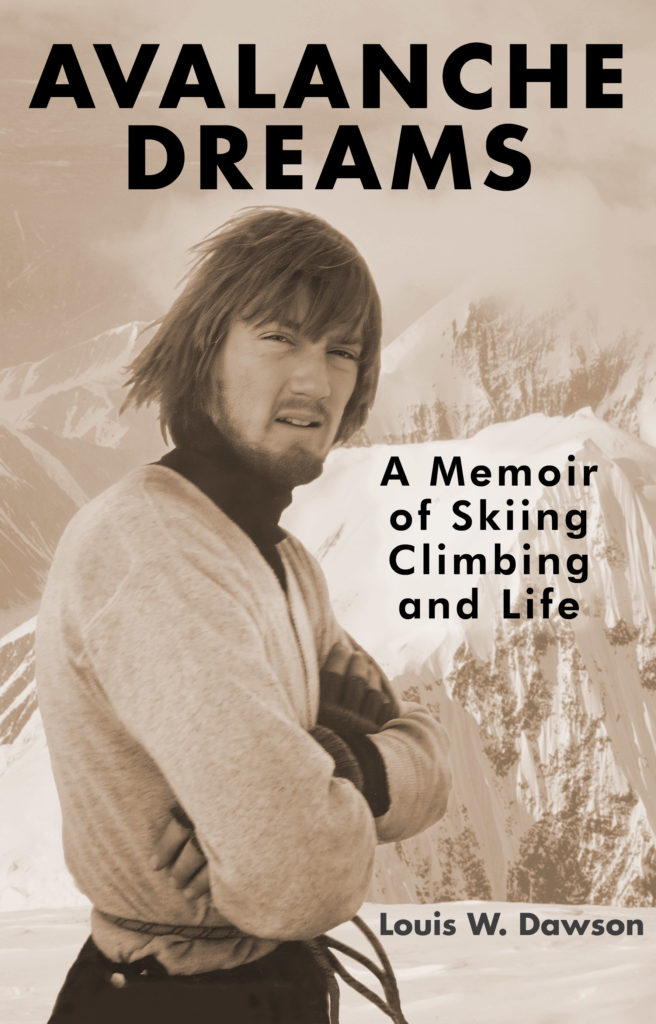

Book cover of Dawson’s newly released memoir: “Avalanche Dreams ultimately unpacks how Lou Dawson became a groundbreaking climber and ski mountaineer while revealing how he became a raconteur of the mountain community.”

Lou Dawson’s memoir, Avalanche Dreams, is a full-circle book exploring ski mountaineering and a well-lived life in the hills.

My dad once flew home with a diamondback rattlesnake in a pillowcase as carry-on luggage. He was returning to Massachusetts after a formative summer in the Four Corners. In one of the more infamous stories he tells of his childhood, my grandmother went bananas and wouldn’t let the snake in the house. It briefly lived in my grandparents’ barn before being sent to school with my dad, where I guess they thought the science teacher might provide refuge. The next day, my father was informed the snake had died. No details were given.

Growing up as a kid on the East Coast, the West was synonymous with adventure. I wanted to escape the deciduous forest for high mountains and become a skier and a climber. I wanted to catch proverbial, if not literal, snakes. The trouble, of course, is that those snakes can bite, a lesson that maybe I am still learning and one that sucks me into stories of adventure and lives lived in the mountains. This lesson is at the heart of Lou Dawson’s new memoir, a story of a life lived climbing and skiing, with the occasional rattlesnake along the way.

Lou Dawson, pioneering American ski mountaineer, climber, and writer, dissects hard-earned wisdom of the mountain in “Avalanche Dreams: A Memoir of Skiing Climbing and Life.” Avalanches are, as Lou puts it, the “sword of Damocles” whispering “rocks, snow, people-all fall.” Lou’s story of his “unrecoverable addiction” to the mountains is a hero’s journey of facing dragons and overcoming Herculean trials to find comfort beneath that sword through partnership and family. He also catches literal rattlesnakes, managing to get his elementary school evacuated when the sheriff comes to kill them.

If you know who Lou is, or if you don’t, his story is a gripping wallop of adventures, family, and gravity.

From left to right, the Dawson family on Mt. Baker: Louie, Lou, and Lisa. Photo: Lou Dawson collection

The Book

The tome opens with the story of skiing Snow Dome atop Canada’s Columbia Icefield. Here, Lou’s voice is joined by Lisa, his wife. Together, they navigate through a whiteout, thread through obstacles and around hazards, and deploy a hefty share of Jerry-rigged wands to mark the way, all the while being encouraged along by fleeting partial views of the objective before them and the subtle contour lines pulling uphill. This story is the ending in the beginning. Lou makes the destination clear but does not hurry us travelers along; instead, he meditates on the intentional backroads taken and highlights the potholes in the path.

What struck me most about the read was Lou’s honesty. He lays bare a complete story of getting to that ski with Lisa on Snow Dome.

Lou grew up in a haze of hippiedom, moving from the east to Texas to Colorado. He highlights the imagination, insecurity, excitement, and dismay in a counterculture beatnik upbringing and recounts stories of Aspen before its glam heyday. Challenges at home fueled a drive towards the outdoors, a theme carried through his story. The high country finds him as much as he finds it.

Early on, Lou gets to know Chirs Landry, finds a mentor in Paul Petzholt, finds an alpine partner in Michael Kennedy, cuts his teeth climbing across the West from Colorado to Yosemite, and is off to races. But quickly, the dark side of the mountains pushes back. As the title might suggest, there is a tension between moving snow and mountains that Lou can’t escape. Kennedy is quoted describing Lou as a ” bold climber with lots of natural ability and a bit of a crazy streak.” Lou plays down the natural ability but expounds on the crazy streak. Climbing stories of success, failure, and close calls paint a picture of Lou’s desire to be an alpinist slowly butting up against an irreconcilable price tag. Headstrong and hungry, Lou wraps up his identity in the outdoors but eventually finds a limit, and his story turns to the search for balance.

Lou constantly contrasts highs and lows in a way that brilliantly mirrors the familiar push and pull of objectives in big places. An early winter ascent of Capitol Peak, often considered the most challenging of Colorado’s fourteeners, is a “fun game” before the trip, but gripped with anxieties as a “risky as hell” reality set in and near-epic ensues. Hindsight is 20/20, but in the moment, rationalization and glory do funny things to drown out reason and fear in an ever-revolving door.

This narrative tension reaches its literal high point with a 1973 ascent of Denali, solidifying a “transcendence of sorts.” Lou becomes an alpinist. After another impressive and, again, epic 1974 winter ascent of Capitol, Lou jokes with a journalist about how he dealt with danger: “We didn’t know diddly about avalanches…” The Capital climb was an impressive first ascent (Slingshot direct) that Lou describes as seminal while pointing out the self-deprecating nonchalance of such pursuits.

Facing a close call with an Avalanche back in Alaska in 1975, Lou beautifully describes the challenge of turning around only to scurry down “like rats racing a flood.” The invincibility inside the minds of young men with ropes motivates Lou’s stories of the vertical world. Close calls cause him to reset but not move on—he embraces big walls, ice climbs, new routes, and eventually skiing. By the late 70s, Lou is, as he says, the poster boy for a “ski-to-die” mentality.

There is a “completeness” to ski alpinism that is hard to explain. Lou does just that. The Elk Mountains and broken bones and big traverses and steep faces are paint brushes for Lou’s story of American ski mountaineering. As Lou finds this progression, it almost kills him.

The story of a 1982 near-death experience in an avalanche is the apex of Lou’s story. The moment feels a long time coming in his telling, but no less harrowing or pivotal. A shattered femur, shattered identity, and shaken outlook on life serve as a turning point. It is the beginning of Lou’s love story.

Family comes into focus as the missing puzzle piece for Lou. He writes about his family in opposition to a fear that family would somehow steal his edge. Instead, he finds family, sharpens it, and gives meaning to his passion. Much of Lou’s early life circles his slow rejection of the spastic outcomes of counterculture reality. He comes to see through it, only to get sucked into an alpine counterculture. After the bill comes due one too many times, Lou steps back and sees this cycle in himself. From pen pals to partner, Lou tells the story of meeting Lisa. He becomes the first person to ski all of Colorado’s fourteeners, he becomes a father, becomes a prolific guidebook author and ski blogger. Family is what gives Lou balance.

Lou Dawson—a timeless capture on Long’s Peak, 1990. Dawson is the first person to ski all 54 of Colorado’s 14th foot peaks. He completed the project in 1991. Photo: Glenn Randall

The Read

Last week, I triggered an avalanche. It was a small D1 soft slab. I was briefly carried but then managed to ski out of it. I brushed it off with the self-aggrandizement of expertise. The runout was clean, the storm snow relatively shallow, and, of course, I stayed on my feet. It was a non-experience. I read Lou’s book and am now embarrassed by my arrogance. It is hard to escape gravity in the vertical world. It pulls everything down, especially egos, fantasy, and exceptionalism. Lou’s story has two parts. One is his path to letting go of ego while embracing creativity and adventure. The other is finding family, partnership, and meaning. Both are his path to living with gravity.

At 360 pages (interspersed with a healthy collection of old-school mountain photos), it is undeniably a behemoth. It also reads as a string of digestible vignettes, mostly chronological, all in service towards a central story. Had you told me such a book about a skier was possible, I would have called BS. If I am going to be wrong, I am too glad for Lou Dawson to be the one to prove it. The book, somehow, doesn’t feel too long, just complete. Though I am sure it helps if you are a fan of Lou’s work and ski mountaineering history or climbing in the American West—I am all three.

The book follows a somewhat predictable arc but remains no less telling. The full story ebbs and winds with gripping near-death experiences but also slow-burn fables of childhood, pitons, and history. Avalanche Dreams ultimately unpacks how Lou Dawson became a groundbreaking climber and ski mountaineer while revealing how he became a raconteur of the mountain community. Lou’s ascendance in the vertical world is a story of discovery, invention, stupidity, and a familiar yet unique dance that brings to mind the words of Dave Roberts, “on the ridge between life and death.” Lou finds himself in a long thread of hardship in the stories of pioneers, ups and downs, and symmetries across mountains and life. This story is special because Lou can look back at a 60-year evolution of perspective.

Lou also gives an amazing and enjoyable account of ski and climbing history that is often overlooked or underappreciated. Fourteener skis, climbing in the West (particularly Colorado), the Trooper Traverse, and early skiing in the backcountry are known stories captured here with a familiarity that is at the furthest only one person removed. This is a common theme in Lou’s work—his earlier book Wild Snow: 54 Classic Ski and Snowboard Descents in North America (out well before Cody Townsend popularized 50 Classic Ski Descents of North America by Chris Davenport, Art Burrows, and Penn Newhard) is my favorite all-time piece of ski mountaineering history. Lou has a knack for blending a good story with the lessons, context, and place that story has in other stories, whether it be his own or the story of ski mountaineering.

The book ends back on the Columbia Icefield. Lou sees everyday life as a “noble challenge,” easily overcome with his family, his rope team.

Two thumbs up.

Available online and soon from a few selected brick-and-mortar retailer.

[Disclaimer: I have known Lou for a while, first as a guest writer for WildSnow back when it was his blog, then as a persistent gadfly who would stop by his garage to see what binding he was taking apart whenever I happened to be in Carbondale. We have skied together]