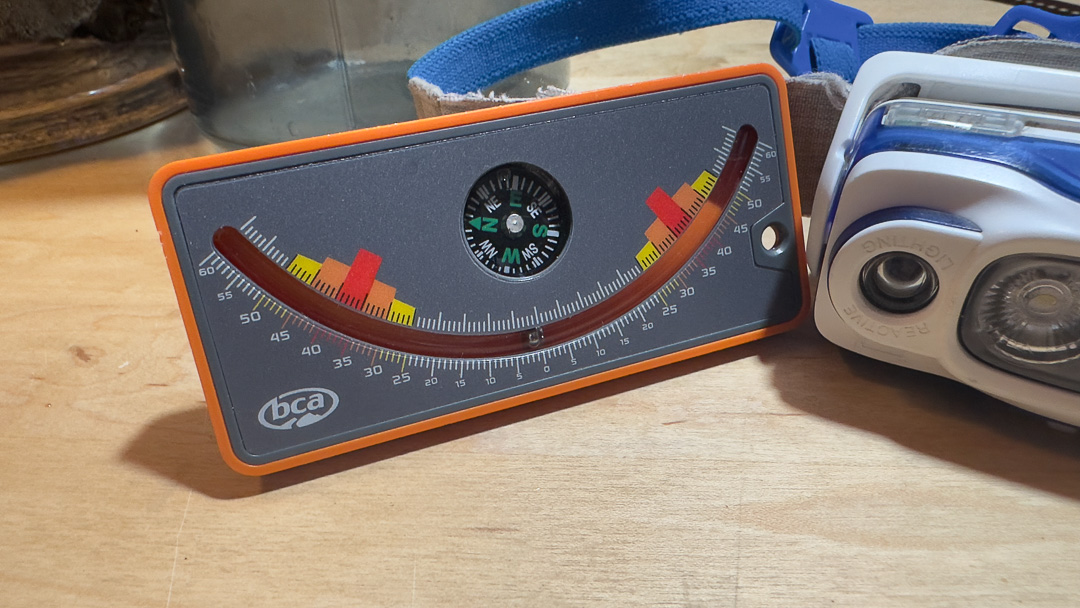

I’d have to dig through my gear—I’m almost certain somewhere in the depths of my enthusiast “snow science” kit is the original Life-Link inclinometer. (Disclaimer—Just because I have no evidence of said inclinometer doesn’t mean it’s not shoved in the dark recesses of a ski pack.) You might know these simple, analog tools as slope meters. With the BCA version, the slope meter uses a free-rolling ball bearing that slides along a track with marks noting the slope angle. This tool, for example, reads upwards of 60 degrees. Many of use the level app on our phones to measure slope angle.

Slope angle—it seems a rather objective dataset. Maybe not.

According to Ian McCammon in a paper titled Slope Measurement for Humans: Inclinometer Error and Risk Communication, “under ideal conditions, currently available inclinometers have a profile measurement accuracy of about ± 4°. This measurement uncertainty, when combined with start zone avalanche frequency and slab extension effects, can result in significant un-intended exposure to avalanche risk.”

I listened to McCammon present his findings at the 2023 International Snow Safety Workshop (ISSW), and you can catch a video of a similar talk from the 2023 WYSAW (video posted below). In short, McCammon highlights how a basic measurement, like slope angle (slope steepness), can be mismeasured and then misapplied when deciding what slopes to ski and what slopes to avoid.

McCammon uses the premise that we are trained to avoid slopes tipping beyond ~35° when snow instabilities might be present. Thus, slope angle becomes a key factor when determining the terrain we seek to ski/ride. Presumably, if a local avalanche forecast calls for heightened avalanche awareness, generally speaking, we avoid the aspects and slopes where these instabilities are likely to present. This means we avoid those specific aspects and the 35°+ terrain. And if feeling more conservative, one might avoid the 30°+ terrain altogether.

Slope Angle—Getting the Measurement Right

Aside from analog inclinometers, many use apps like Gaia, CalTopo, FatMap, and onX and default to using slope angle shading in those tools. McCammon reminds us that our apps’ slope angle, despite the reliance on high-tech magic and Lidar, can vary by as much as +/- 6 degrees. If we count on sending lines no greater than 35° and wholly rely on a navigation app for slope angle information, know this data could be way off. This means that you could be entering terrain you think is under 35° when, in fact, it is greater.

Take the time to measure slope angle in the field.

McCammon has some compelling data when it comes to measuring slope angle using an assortment of available tools under what he calls “ideal” conditions: “in a warm classroom, with an unambiguous image projected on a large screen and measured with their own inclinometer. I minimized parallax errors by ensuring measurements were made perpendicular to the center of the screen. I also asked participants not to share results until after their measurement forms were handed in.”