We prefer to ski and climb. But understanding how the sweet ski sac on your back involves geopolitics and trade can be informative, too. This headline came across last week’s news feed: “Black Diamond Testifies Before the House Ways and Means Committee in support of Several of the Industry’s Trade Priorities.”

I know—not exactly the headline that should have gotten my attention. Around the same time, headlines roared Kelly Slater saved himself by making a mid-tube recovery. No doubt, some headlines swooned about line-sending in South America. I digress. However, Black Diamond Equipment in the news catches my eye, even more so when testifying at the highest levels of government.

Black Diamond Vice President for Operations, Fabian Garza, represented BD and members of the Outdoor Industry OIA) of America in lobbying for, among other things, the renewal of the Generalized Systems of Preferences (GSP).

Let’s make a few things clear upfront. Companies like BD and pretty much any outdoor brand are interested in the GSP. The GSP is the heady title for the details wrapped up in a trade agreement. The Congressional Research Services states the GSP “provides nonreciprocal, duty-free tariff treatment to certain products imported to the United States from designated beneficiary developing countries (BDCs).”

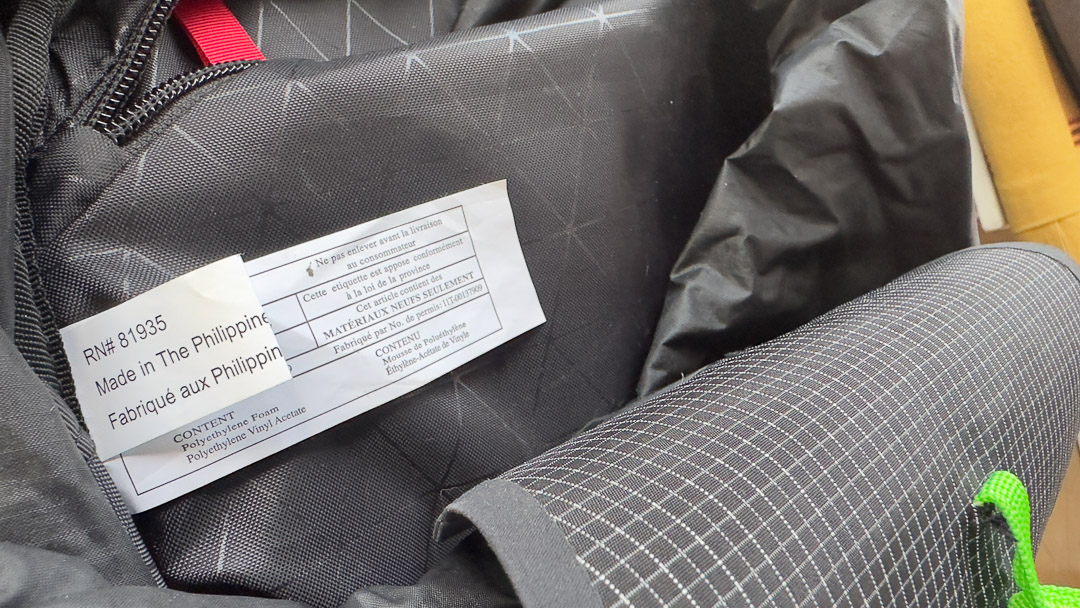

Practically speaking, this means, for example, that a backpack manufactured in Vietnam can be imported to the US with zero to no tariffs. The GSP, in principle, keeps costs down for the exporter, importer, and finally, you, the consumer. The GSP expired on Dec. 31, 2020, and has not been renewed. Thus, Garza’s presence in D.C. speaking on behalf of BD and the OIA.

In his testimony to the House Ways and Means Committee, Garza claims since the GSP expiration in 2020, the outdoor industry has been burdened with an additional $1.65 billion in tariffs. (That’s a lot of chalk bags.) Among a few ways an outdoor company can handle those extra costs is to absorb the cost internally and not increase prices, or the costs of increased tariffs are passed onto the customer. Let’s also assume that there’s some middle ground: the company can absorb some costs and transfer some to the end consumer, which is you and me. Further, the OIA, and by extension, companies like BD, are asking for retroactively reauthorizing the GSP. That means companies hit with a tariff since the GSP’s expiration—that otherwise would have been negated under the GSP—can apply for a refund from the U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

A Snapshot: Most backpacks we consider technical sacs fall under “Travel, sports and similar bags with outer surface of man-made fibers.” According to the Congressional Reporting Service, $616.7 million of these products (HTS # 4202. 92. 31) were imported from GSP qualifying countries in 2021. With the expired GSP, these products were hit with a 17.6% tariff rate. Had the GSP been renewed, the products would likely have been imported duty-free.