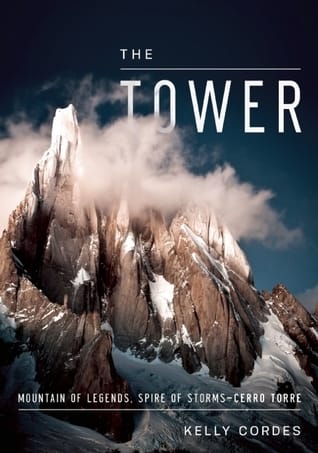

The Tower focuses on Cesare Maestri’s claimed first ascent of Cerro Torre. Maestri and his supporter and partner, Cesarino Fava, maintained that Maestri and Toni Egger, who did not survive the climb, reached the summit. Cordes does a damn good job bringing the evidence to bear. Yes, this is the same Cesare Maestri who later used a gas-powered compressor to bolt what was known as the Compressor Route up Cerro Torre—a virtual ladder up the mountain.

Maestri’s bolts were later chopped by Hayden Kennedy (RIP) and Jason Kruk, who climbed the route without them. The book focuses on these two events, thus delving into wider and deeper issues of how and why we climb and how we tell the stories we do about our climbs.

My interest in this book is not the climbing; it is our take on truth, especially when it comes to our internal storytelling. There is a place where an inner truth becomes more apparent and less slippery. These are places of adventure where fear resides: Places where, alongside the possibility of triumph and joy, there are possibilities of feeling shame, humiliation, darkness, doubt, failure, and chances of injury or death. In these places, some internal rudder shifts, a scale whose balance swings, a wooden ball rolling against a wall in a pitch-black room. Thunk. And in that moment, a truth about yourself stands so clear as to be undeniable. It may not be what you hoped to find. Then again, it may be even better than you allow yourself to hope because, in either case, there is something more important to us than truth; that is protecting the story we tell about ourselves. That inner running babble of our life’s chronicle.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.