Vivian Bruchez, Jules Socié, and Aurélien Lardy make their mark in the Chalten Massif as they repeat an Andreas Fransson test piece.

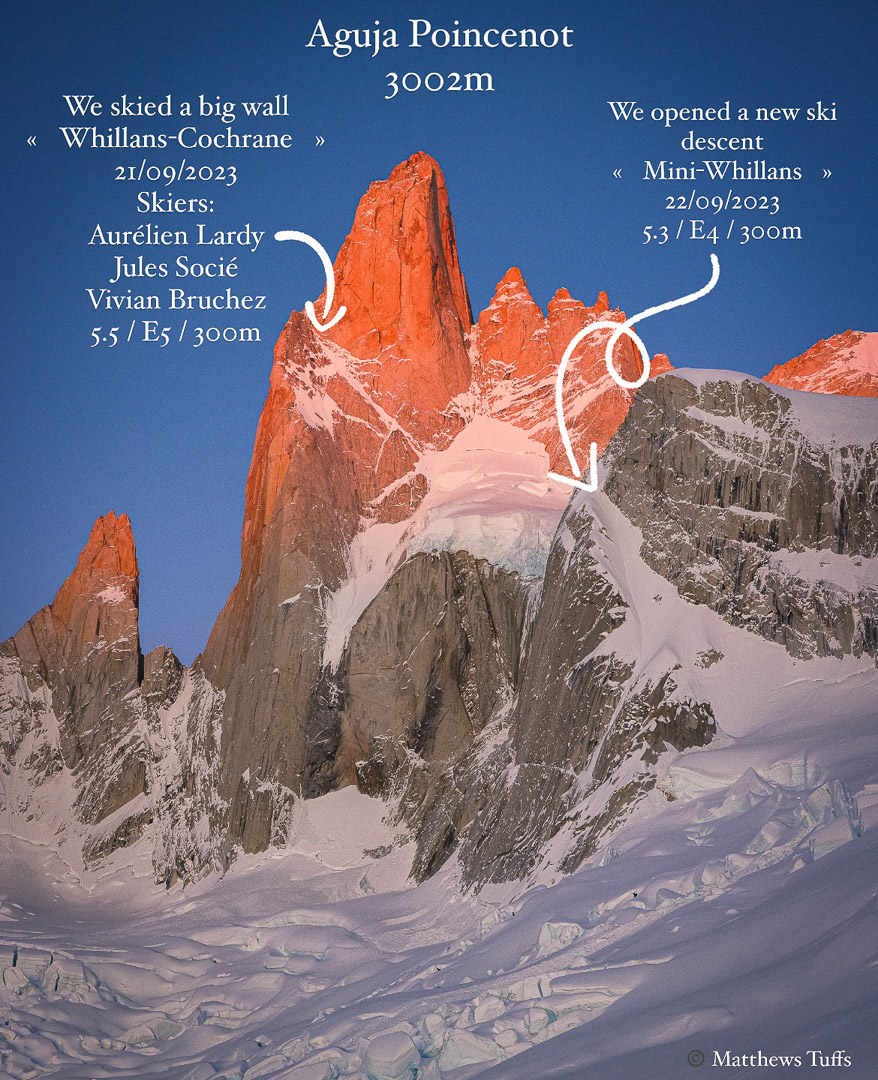

Oftentimes, the camera lens can skew the difference between absolute and apparent steepness. Sure, a line might be steep in reality, clicking into tiny tech bindings, staring at a 55+ degree slope with an ample abyss just beyond the roll over. Yet photos, sometimes, don’t do it justice. That wasn’t the case Thursday when French ski-mountaineer Vivian Bruchez posted on Instagram about his September 21 ski descent on Aguja Poincenot, in Patagonia’s Chalten Massif, with partners Jules Socié and Aurélien Lardy, which they then followed with a new line on September 22. The images posted make the stomach appropriately uneasy—this is steep skiing from any perspective.

Aguja Poincenot was first climbed in 1962 by Ireland’s Frank Cochrane and the UK’s Don Whillans via what is known as the Whillans-Cochrane route. One aspect of the route, known as the Whillans Ramp, is a long, exposed, and steep thread of snow bisecting the mountain’s east face. Aside from the ramp and hanging snowfield below, this is a big wall theater visited by alpinists and, sometimes, the imaginations of ski mountaineers.

The line was first skied in 2012 by legendary skier Andreas Fransson. (You can read about Fransson’s thoughts on the ski line here. It is truly an excellent read.) Fransson considered the descent, which he skied solo, one of his most, if not the most, technical descent he had skied. This is of note considering his legacy of steep skiing, including Denali’s South Face in 2011, which was filmed by Bjarne Salén—the same Bjarne of The Fifty Project.

Salén accompanied Fransson to the base of the Whillans Ramp in 2012—from there, Fransson quested off alone.

Bruchez, Socié, and Lardy completed the second descent of the storied ramp on the 21st, while the following day they opened new adjacent ski terrain, calling it the “Mini Whillans.”

“This is the ramp of ‘the end of the world,’ we were not here to find the limit; we were here to live the total experience. We were not there to count our turns, but more there to share a unique ski descent! Be in the right place, in the right moment, with the right people!”—Vivian Bruchez

Bruchez noted on his Instagram that Fransson had described the descent as “the steepest and most exposed I’ve had the opportunity to ski.”

In his thoughts about the line, Fransson wrote about style, ego, and who, in the end, he skis for. Fransson set some context by explaining that he had sideslipped some and rappelled roughly 15m.

“But when we are arguing about these things we have kind of lost the thin red line of purpose in the first place,” wrote Fransson. “If we are thinking of these things, then there is a risk that we are playing this game for others and not for ourselves. Is it worth risking your life to make others think you are cool, a great skier, have courage, are a great alpinist or something else?”