If you are reading, listening to, or viewing an avalanche forecaster or educator discussing the local snowpack totals—pre and post storm—you’ll often hear the term “SWE” used. SWE is short for snow water equivalent and provides a reading of the available water in the snowpack. SWE estimates help regions reliant on snowpack (and a normal to high SWE) for water plan for ensuing water shortages or, in the case of California’s Sierra last winter, an ensuing deluge once the sun begins arcing higher in the sky.

We skiers and riders associate a higher SWE with more snow on the ground. It also follows that a storm depositing loads of snow, say, 12”-24” but with a corresponding low SWE, means light and fluffy snow—Utahns already know this.

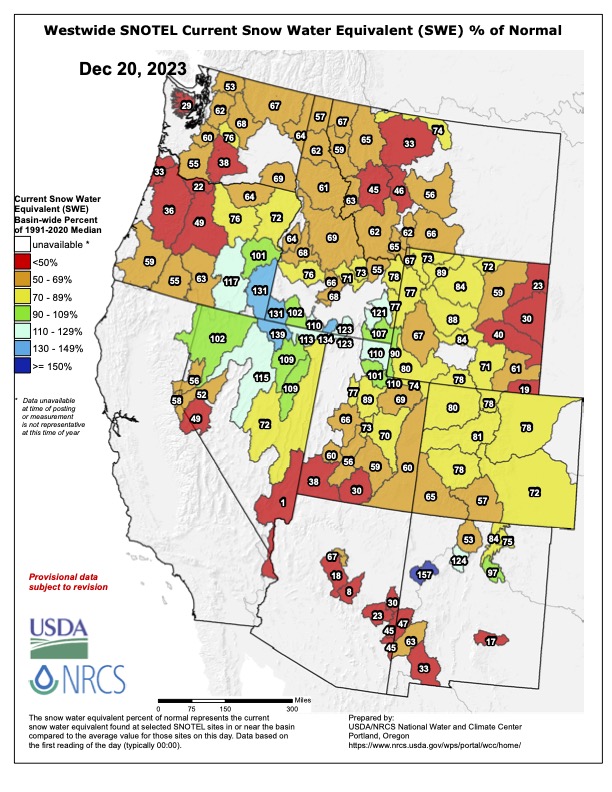

In today’s survey of the snow scene, we take a broad look at SWE across the West. The board look provides an idea of how the backcountry ski season has played out thus far for many, and insight into the burgeoning stress some municipalities and agricultural zones may be experiencing as high and dry seems to be a predominant theme as the Northern Hemi begins a meek spin towards the winter solstice.

Several of us at The High Route have gotten to know the less important, though still a bummer, consequences of low SWE: core shots. Note—it may still be rock ski or board season where you are; proceed cautiously, as the tides are not high.

Following is a series of maps displaying current SWE as a % of normal. Yes, it’s kinda grim. But the glass is half full; the season remains early. A few springs ago in the PNW, the SWE was looking mighty grim rolling into spring; then cold temps, persistent moisture, and excellent turns ensued as the mountains experienced a mighty fine SWE rebound. Noted. Currently, Alaska looks SWE-rich and Nevada looks relatively good.