inReach/lighter for scale. For me, this first aid kit strikes a balance between well stocked and compact/lightweight.

First aid kit contents are one of the more varied/contested items among ski touring partners and communities. From the legendary French guide’s first aid kit: two cigarettes and a cell phone, to a seasoned guide/search and rescue member who has seen too much and prepares as such, there is a huge variety of kits that folks are carrying.

In this series, we will explore both extremes and more middle-of-the-road kits that various folks carry during their day-to-day skiing. The goal here isn’t to provide a definitive kit for a reader to copy for themselves but rather to give context and a framework for building a first aid kit that matches your location, risk tolerance, medical training, and personal needs.

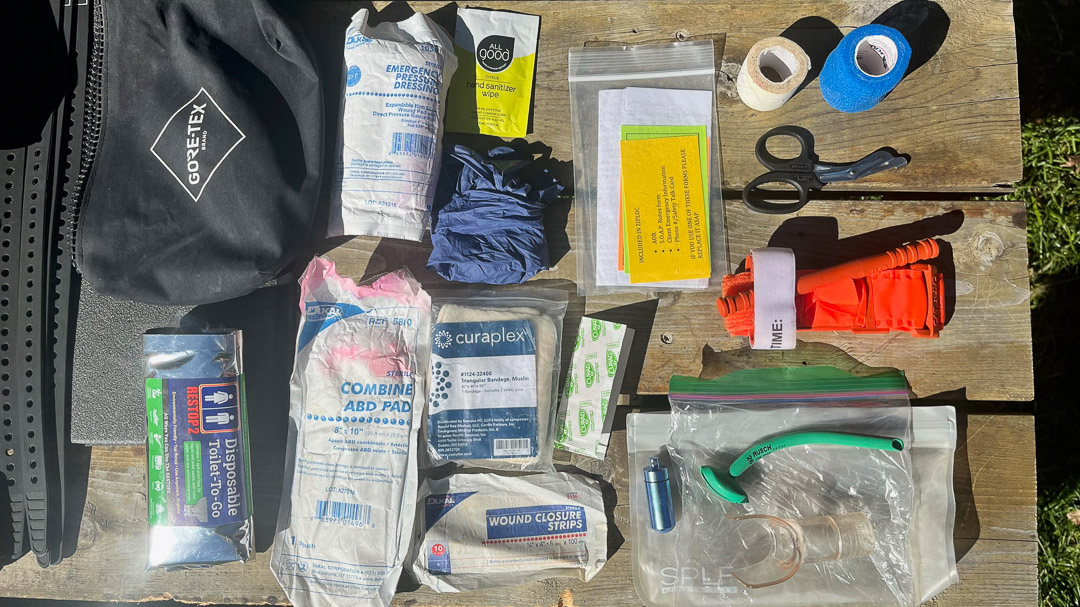

The full spread: most of this fits in the Gore-Tex bag, then a few bulkier/multi-use items live elsewhere in my pack.

Perhaps the most critical component of any first aid kit is medical knowledge and training. Something like a nasopharyngeal airway device isn’t much use in your kit if you haven’t been trained on its proper use and application. Two points here. First, don’t carry things you don’t know how to use. Second, basic first aid training is worthwhile. Courses like a WFR or WFA will teach you the necessary framework for assessing a situation, identifying the necessary treatment/evacuation plan, and communicating the patient’s needs to rescuers. Feeling empowered by (some) knowledge in a scary situation is worth its weight in gold, in my experience.

With super professional Search and Rescue teams like Air Zermatt around, a first aid kit in the Alps can be pretty minimal. Photo: Air Zermatt Library

Below are the contents of my personal first aid kit. This is the kit I carry both while guiding and recreating here in the Tetons. I reassess my kit every 2-3 years, usually while recertifying my WFR. For me and my WFR training level, I find this kit strikes a good balance between well-prepared and lightweight. Here in the Tetons, we are very fortunate to have the excellent Teton County Search and Rescue, as well as Jenny Lake Climbing Rangers, ready to help when things go wrong. They are incredibly professional and have a generally quick response time, but given the remoteness and weather variability of the Tetons, we need to be prepared to bear down and deal, potentially for many hours or overnight. The access to highly trained mountain rescuers fits us, in my mind, somewhere in the middle between a mountain range like the Alps, where rescue is often minutes away, and an extremely remote range like the Beartooths, where Search and Rescue teams have minimal resources, and the weather can be incredibly harsh.

My personal backcountry first aid kit:

- Gore-Tex zipper pouch about 6”x 9”x 2”

- Small ziplock with SOAP note, mini pencil, emergency response plan

- 2x Body warmers, stick on 3×5” chemical warmers

- Extra WAG Bag

- Mini trauma shears

- A couple pairs of latex gloves

- Meds: Benadryl, ibuprofen, chewable baby aspirin (all in a little pill case from Amazon)

- NuMask CPR Mask

- Nasopharyngeal Airway device (NPA)

- CAT Tourniquet

- Cloth tape

- Coban/Vet wrap

- Triangular muslin bandage

- Abdominal gauze pad (Large absorbent gauze)

- Pressure dressing gauze roll

- Wound closure strips

- Band-aids

Note: Not in this kit, but in my pack: foam pad for ground insulation/splinting, firestarter and lighter, guide tarp or rescue sled for shelter, 4 voile straps, a Garmin Inreach, and often an *extra* puffy layer such as an Arc’teryx Cerium LT.

I like to think of my kit in terms of likelihood of an event/injury and specific needs for said emergency. In some cases, there are low likelihood scenarios that also have a negligible weight penalty to be ready for – why not be prepared in that case? A few key points/thoughts on my kit:

Packaging the Patient

In any winter emergency, packaging and warming the patient is absolutely critical. Ground insulation, chemical warmers, extra layers (beyond what you may need to stay warm as the rescuer) and some sort of shelter are all part of this system. In a more remote area, an inflatable sleeping pad and more warm clothes like puffy pants and a true parka may be warranted.

Prepared for Trauma

As far as incidents, I view trauma and avalanche burial as the most likely events that I can be prepared for. Trauma can have a large range of mechanisms of injury—a fall, rockfall, avalanche, crampon puncture, etc. Generally, I want to be prepared to control bleeding and build basic splints: this should cover most traumatic injuries we encounter ski touring. In my last WFR recert, I was convinced to add a CAT tourniquet to my kit – many view a tourniquet as improvisable, but the width and pressure adjustability of a real tourniquet are hard to replicate and important for better outcomes when needed.

- In the case of an avalanche burial, I carry a NuMask cpr mask and NPA to provide rescue breaths and to establish a reliable airway. Beyond resuscitation needs, trauma and packaging applies as above.

- Meds to treat some common medical emergencies are lightweight insurance. Obviously my med array isn’t robust – but a few basics could buy some time in a medical situation.

I’m excited to dive into this topic more as the season progresses. I am well aware that I am not an expert on the subject, so I hope to learn some valuable information to add to my knowledge and kit. It will be interesting to see different takes on the kit, as well as to see what other folks “in the middle” with me are carrying.

My winter FA kit for work looks really similar. The one major thing I add to Gavin’s selection is a Hyfin vent (pre-made occlusive dressing). This lives in my FA kit when there’s a chance of penetrating injury. The MOIs for that in my mind are either an accidental gunshot wound during hunting season, or penetrating trauma during a high velocity impact (ice tool, tree branch, etc). For that reason, I carry the Hyfin vent during hunting season, during the winter while skiing and ice climbing, and during the summer while mountain biking.

I also have occlusive chest seal dressings in my hip pack that I keep in both of our cars to address trauma on the road, but I don’t carry one skiing. It’s far too specific, kinda finnicky, and can cause problems. They were developed for time-critical situations with gunshot wounds in mind, but aren’t well-suited to prolonged use and I’d caution against them.

The occlusive chest dressing is meant to address a sucking chest wound; a rare scenario in which the lung itself is not punctured, the chest wall is, and the wound itself makes an only-in ball valve that causes progressive tension pneumothorax with each inward breath. The problem is that a muuuuch more common issue is the chest-wall-wounded, lung-also-wounded scenario. In this setting, applying an occlusive dressing can CAUSE a tension pneumo as air escaping from the lung is trapped within the thorax by the dressing.

The rare scenario that is addressed by the chest vent dressing can be instantly fixed by enlarging the wound (takes some experience or understanding to have the confidence to do that). In the rare case that someone is struggling to breathe with the one unaffected lung, a hand over the hole (or duct tape) will do.

You can hang on to the Hyfin Vent and use it if needed, but the crucial thing to know is that if you have it on a chest wound, and there is progressive difficulty breathing or loss of consciousness, it’s time to immediately remove it and stick your finger in the hole. Pssssssssssssssss……

Anyone know where you can buy a NuMask? I have never been able to find any for sale.

Hey Slim, That is an excellent question. I’ve heard rumor that the gentleman behind NuMask closed up shop some time ago. I went hunting last fall and came up empty handed – I’ll do a little more digging. You certainly aren’t the only one looking; the NuMask is an excellent tool and much more effective than a standard pocket mask

thoughtful collection of supplies. thanks for sharing. I opt for an inflatable mat considering the likelihood of staying put and waiting for help rather than packaging a patient and sledding them out. the triangle bandage is a curious [and what I perceive as redundant] addition. would like to hear your thoughts on that inclusion. although perceived by some as excessive in the first aid kit realm, Id be interested to hear about your blister care kit & routine (if any in particular beyond tape and a grimace). all in all thanks for the informative post

I feel like the discussion of blister care has to be separate from first aid, particularly trauma care. Some people are blister machines, others never have them. My answer to this issue is to carry a small roll of Leukotape, which is a superior non-stretching orthopedic tape, in my kit. I view this a potentially repair material as well, and it can patch up most blisters enough to get back to the truck.

I think Gavin did a great job here of being prepared to manage the most common, serious backcountry issues that we are capable of intervening upon with minimal kit. To my mind, this is CPR after avalanche/lightning, life threatening bleeding, splinting of long bone injuries, basic airway management after trauma, and hypothermia. For those with medical licensure, an 11-blade scalpel and 6-0 endotracheal tube could round this out, and some wound consider adding an epi-pen depending on the group. The problem with expanding scope beyond this kind of care is that you can prepper yourself to death and end up with a kit nobody would ever carry.

Personally: CPR mask, SWAT-T tourniquet, space blanket, israeli trauma dressing, NPA/OPA, 6-0 ETT, 11-blade, leukotape, safety pins, knife. But that’s my kit where I can reach a road within 1 hr of normal travel and have reasonable cell service. My hut kit and meds are quite different.

I dont often suffer from blisters, so I don’t tend to carry much blister care stuff day to day. The best blister care kit ive seen involves leukotape, compeed blister patches, and tincture of benzoine to get it all to stick.

That is a great setup! Having been a SAR team member in Colorado for almost 6 years, I would suggest the addition of a SAM splint (with roll of Coban) and a space blanket or other high efficiency/lightweight emergency bivy to compliment heating pads and other insulation. Field medicine can make all the difference, but no matter what, getting the subject evacuated to higher level of care is going to be the most important objective to work towards. SAM splints are going to be much more effective than most field fabricated splints for stabilizing extremity injuries. And aside from managing ABC’s, E (environment) may be one of the most important factors to manage and D (disability) can help reduce the time component and other secondary injuries/issues from manifesting.

Knowing how to use NPA/OPA’s is important, and they can be great tools, but one must also know when not to use them is also critical.

Want to emphasize the role of a satellite communicator as being an integral part of the medical kit, regardless of its form factor. I have seen some discussion on other forums about the number of communicators that are necessary to have in a group, with some feeling like one per group is acceptable to be more efficient with gear distribution. Relying on one device assumes that the person carrying that device is not the one who falls, splits off and gets lost from the rest of the group, is buried, or the device is inoperable to due damage or a dead battery.