Let’s take the time machine way, way back. Ötzi the Iceman, who crisscrossed the Alps, is said to have carried a pack—it looks like an iterative form of a frame pack. Estimates pin down Ötzi’s ramblings at roughly 5000 years ago. Although rudimentary in design, we can assume Ötzi’s pack allowed him to haul more weight more efficiently had he had no pack.

Despite our reliance on backpacks, still, thousands of years later, a Colin Haley quote sheds light on pack design over the years—”it’s 2000 year old technology…amazing how pack manufacturers can still screw it up.” Following along with the socials the past few months, it might seem Haley’s 2000 year wait for a more perfect pack is over.

This is all to say that packs have improved over time. And the market’s diversity means you should be able to find a pack that suits your peculiarities. I prefer a side zip and roll top for main compartment access. I prefer no frame and just a simple foam back panel for comfort and structure to carry loads up to, say, ~20 pounds. I now use packs with no load lifters—both for day trips and multi-day traverses—with no complaints.

My 70L multi-day pack weighs ~1150g. My single-day ski pack weighs ~625g. I like these packs because they are simple and meet my needs for stowing and carrying. And they are light. At these weights, I’m still not compromising on comfort and features (except for wanting full side zip access on the 70L pack).

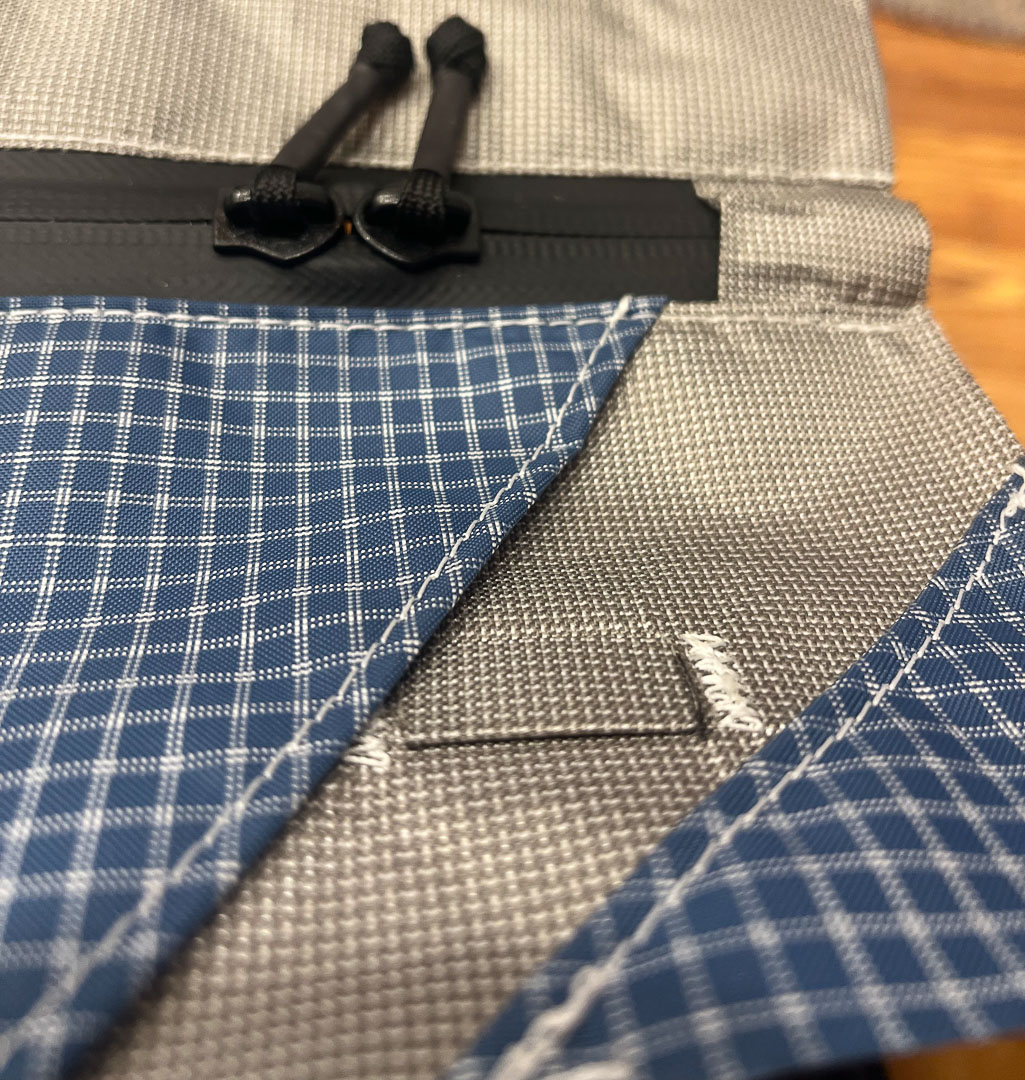

Part of the overall reduction in a pack’s overall pack weight, generally, is due to the use of lighter fabrics that are often more durable than more traditional pack fabrics.