I sense that over the time I’ve been reading and assessing different avalanche forecasts (I’ve spent a decade roughly each in Montana, Colorado, and Oregon), they have trended towards more graphical representations and less text. In other words, it is relatively easy for those who choose to digest critical portions of an avalanche forecast to forgo reading any text. Look around the ski group in the early AM and note the number of fast-scrolling index fingers—no way folks are digesting the text portion of the forecast. Some details are likely missed as they scroll through the forecast.

The trend is towards simpler ways of communicating avalanche forecasts.

After six years of internal use and a season of limited public use in 2022-2023, the Swiss Avalanche Warning Service will add sublevels to their avalanche forecast this season. Yes, they are adding complexity, which seems to be bucking the trend. In Europe generally, including Switzerland, forecasters use five discrete levels to define the avalanche danger level.

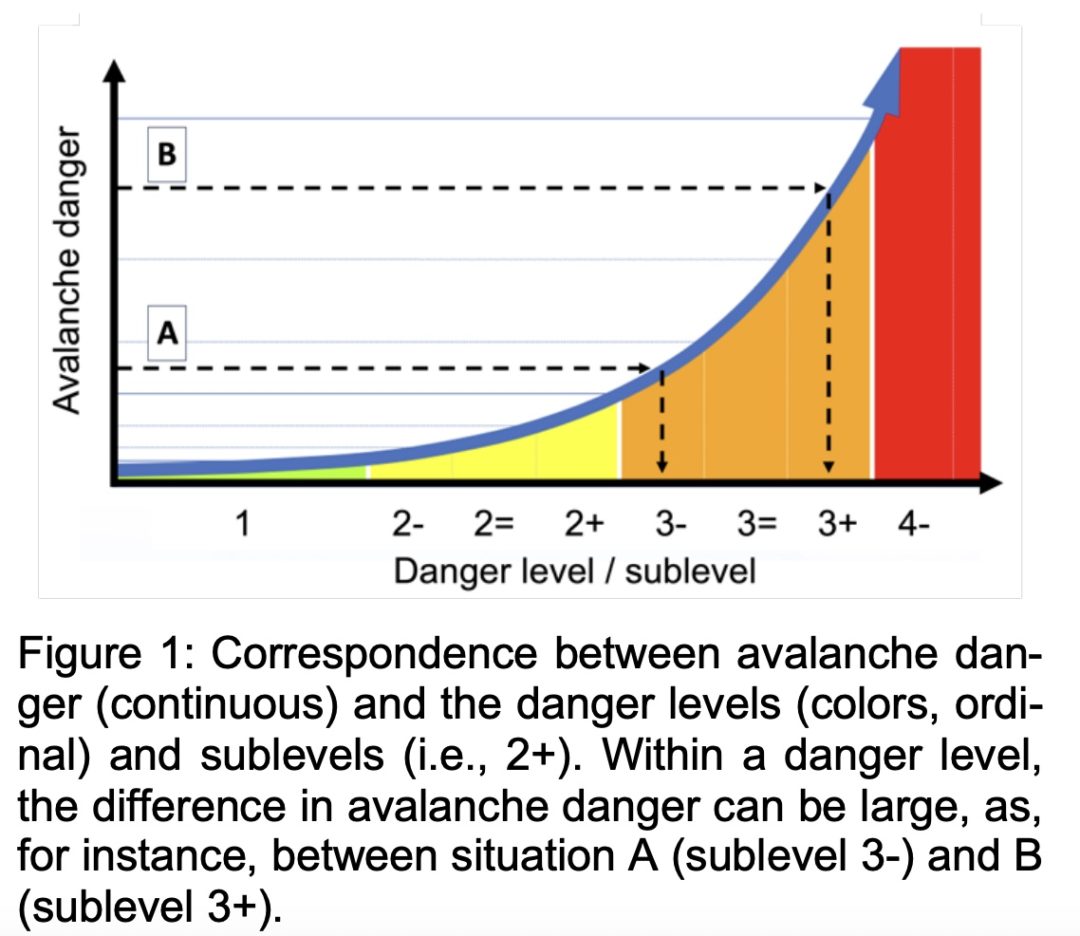

This season, instead of a straight 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, the danger levels will include 1, 2-, 2=, 2+, 3-, 3=, 3+, and 4-.

In an ISSW proceedings paper titled “Introducing Sublevels in the Swiss Avalanche Forecast,” representatives from the WSL Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research SLF in Davos, Switzerland, discuss the adoption of sublevels, which, on the surface, requires users, like backcountry turn seekers, to understand a more nuanced danger rating scale.

The authors reason the move to sublevels and away from their traditional five levels this way: “This simplification of a complex, multi-dimensional natural phenomenon into a small number of discrete classes inevitably leads to a loss of information. Moreover, in many countries in Europe, the forecast danger level (DL) is either 2 (moderate) or 3 (considerable) on about 75% of the forecasting days.”